Excellence in Science and Society: Considering Gender.

| EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT President of the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality |

| CYPRUS UNIVERSITY – EQUALITY COMMITTEE | |

| “EXCELLENCE IN SCIENCE AND SOCIETY: CONSIDERING GENDER” | Lefkosia, 14.11.2003 |

I feel great joy and honor for the invitation you extended to me to speak to such a distinguished audience at the University of Cyprus. I would like to warmly thank the Equality Committee, and I wish them success in the work they have started at the most appropriate time, a few months before Cyprus’ accession to the European Union as a full member on May 1, 2004. It is a pity that one of the key figures in Cyprus’ European journey, the late Yiannos Kranidiotis, did not live to see his vision become a reality. Now that the pre-accession phase is coming to an end, there are many thoughts and emotions, both numerous and intense.

I would like to take this opportunity to emphasize that the significance of a country’s accession to the European Union is not only found in the substantial economic advantages it will gain, but also in the social benefits derived from interacting with the European multinational and multicultural environment, as well as the contemporary currents of thought and action.

In this context, special efforts need to be made to promote women’s rights and gender equality in all areas of economic, social, and political life. For this reason, I consider the creation of the ad hoc Equality Committee at the University of Cyprus to be particularly important, as specialized activity within the academic environment can have multiplying benefits for women, both within the university and in Cypriot society.

At both the European level and at the level of member states, significant initiatives have been undertaken to facilitate the full integration of women into the economic and social life of European countries, particularly in those areas from which they were previously excluded, such as science, industry, and technology. This effort has only begun in recent years. Unfortunately, despite UNESCO’s recommendation in 1984 to the European Community to keep statistical data on the gender distribution among scientific personnel in Europe, this process did not actually start until 2001. [1]

It is a widely accepted fact that women, when placed in conditions of true equality and meritocracy, perform just as well as or even better than men. For example, in most European countries, there are more female university graduates than male (in Greece, 62% of university students are women). However, despite this, the scientific staff in European universities, particularly at the higher ranks and in decision-making bodies, remains predominantly male.

The obstacles that women face when they complete their studies and seek employment are numerous and often insurmountable, and they are primarily rooted in the very structure of our modern societies. [2] European societies have been shaped, and to a large extent continue to function, in ways that exclude women from positions of responsibility. In the latest report by Eurostat, it is noted that in Germany, the gender pay gap is 17% in the public sector and 20% in the private sector, while in the UK, for the first time in 20 years, there was an increase in the pay gap between women and men in 2002. In many European countries, women are overrepresented among the poor and the unemployed, while they are absent from managerial positions. It is particularly striking that in the most significant discussion held in the Union in recent years, the debate within the framework of the Assembly for the new Constitutional Treaty, there were only 17 women out of a total of 105 members.

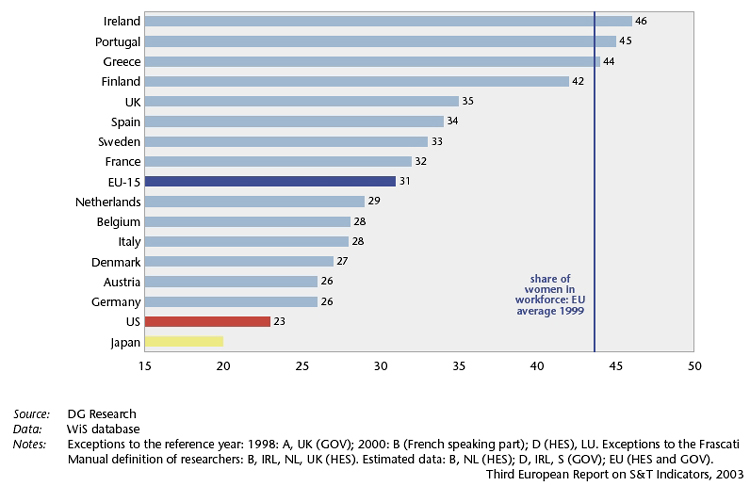

The European scientific community is a reflection of the reality prevailing in each sector. In Tables 1 and 2, we can see the percentage of women employed and working as researchers in higher education institutions across the EU member states, the US, and Japan, as well as the corresponding percentage in government positions. [3] We observe that, in both cases, the European average for women is only 31%. It is interesting to note that four member states—Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Finland—have female researchers in percentages exceeding 40%. In countries with relatively newer institutions and universities, such as the aforementioned four—and Cyprus as well—women have found the opportunity to showcase their abilities and claim recognition. In contrast, in countries with established systems in education and science, despite the quality of the scientific work produced, men dominate. Germany, being last on the list, is a very characteristic example. [4]

An extremely interesting aspect is the distribution of scientific fields between women and men. Recently, I had the opportunity to conduct an extensive study on this subject as part of preparing a report on the participation of women in the new information society, which was recently approved by the European Parliament plenary session. One of the central findings of the research is the direct interdependence between the difficulties women face in the workplace and the choices they make during their education. Inequality in education leads to inequality in employment, and consequently, inequality in pay and living conditions. [5]

In today’s era, the educational system and academic community prioritize the development of the sciences and modern technology. A clear indication of the significance of new technologies in the context of the New Economy is the fact that 80% of the new job openings in the European Union in recent years are related to new technologies. However, women appear to avoid exactly those fields that could offer them greater professional career opportunities, instead preferring more theoretical scientific disciplines, which are linked to higher unemployment rates. From secondary education onwards, girls and boys begin to differentiate in their subject preferences. In higher education, women make up only 20% of computer science students in the European Union,[6] male graduates in the natural sciences outnumber female graduates by two to four times, while women represent only one-third to one-quarter of the research staff in natural science laboratories.[7]

The causes of this differentiation are found in social factors related to stereotypes and prejudices that discourage women from engaging with technology and the sciences, limiting their choices and placing barriers in their careers. [8] As early as 1985, research by the British Equal Opportunities Commission showed that the very structure of the curriculum is responsible for the small number of women who prefer technological directions. [9]

This reality is likely to have its effects on the professional field as well. Thus, only 14.5% of new media entrepreneurs are women, despite the fact that the target of 40% was set in the Fifth Framework Programme for Research and Technology of the European Union. [10] Similarly, most women working in the field of new technologies are employed in less demanding tasks, which require less specialization – such as text processing and data entry – resulting in lower wages, less professional security, and fewer opportunities for advancement. Men, on the other hand, dominate among senior executives who occupy creative positions in software production and systems analysis. [11]

Even women who choose to pursue careers in the sciences fall victim to discrimination compared to their male colleagues. In a recent report by the European Commission titled “Building Excellence through Equality,” it is noted that female scientists face discrimination in terms of their salaries (they earn lower wages than their male colleagues), the type of contracts they have (most fixed-term contracts are held by women), their career advancement (which is delayed, more difficult, and rarer than that of men), while they are almost entirely absent from the highest ranks, rarely receive recognition for their work, and are largely excluded from prestigious institutions. [12]

These discriminations are certainly not based on an objective assessment of women’s abilities, but rather on prejudices and stereotypical behaviors against women. The results of a study conducted in the USA on the “productivity” of male and female scientists, using the quantitative criterion of article publication in scientific journals, are telling. The study found that the majority of unpublished articles were written by women, while, conversely, the majority of published articles were written by men. Therefore, women conduct research, produce work, and wish to present it to the scientific community. However, this opportunity is not granted to them by the male-dominated establishment, which makes their professional advancement more difficult and perpetuates the discrimination against them. [13]

It thus becomes evident that, although the progress women have made in recent years in every field is significant, there are still many important steps to be taken to achieve true equality. To reach this goal, it is initially necessary to give the required emphasis to the legal institutionalization of gender equality in all sectors within the Union. Our goal is for all new legislative texts, both from the European Union and from the member states, to incorporate the principles of equality. Therefore, despite the small representation of women in the work of the Constitutional Assembly, a series of notable parallel discussions and interventions took place, both from the European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights, as well as from the European Network of Parliamentary Committees on Equality and from organizations across Europe, presenting proposals that facilitated the work of the Assembly, while simultaneously integrating gender equality into the new Constitution of Europe.

The European Commission has set as its goal the consideration of the gender dimension in the Sixth Framework Programme for Equality, covering the period 2002-2006. The measures it promotes include the collection of statistical data on gender distribution, so that, through a better reflection of reality, a deeper understanding of the issues can be achieved and more effective methods for solving them can be developed. Additionally, through European networks of women scientists, their ability to access more and better information about their field of study, as well as situations and problems common to women scientists across Europe, is expanded. The completion of the study that will provide recommendations aimed at creating a European Platform for Women Scientists will be a very important step in strengthening the position of women in the European scientific community. Special mention should also be made of the Helsinki Group on Women and Science, which, since 1999, has significantly contributed to highlighting the need for broader female participation in research, through the exchange of views, experiences, and best practices. [14]

However, beyond the work carried out within bodies or groups that are part of European institutions in one way or another, it is necessary to create the right conditions within the family context. Women interested in their professional careers face, at some point in their journey, the dilemma of choosing between family and career, known as “choose-or-lose.” Despite the differences observed between European countries, generally speaking, the data shows that in many countries, female scientists are less likely to have a family, and in any case, they pay the price for their choice – either not having children or not having the career they desire. In contrast, having a family seems to positively affect a man’s prospects for career advancement. [15] It is characteristic that men with three or four children are much more likely to rise to the highest ranks of their profession compared to men without children or a family. The exact opposite is true for women. That is, women with three or four children are found at the lowest levels of the hierarchy, while childless and single women are at the highest. [16]

While it is a common belief that for some women, the inability to advance professionally is the result of choices related to family, no one has thought to link the inability of some men to advance professionally with specific choices of a similar social nature. The absence of such reflection highlights the vast scale of the problem, as it is still taken for granted that the woman will bear the greater part – if not all – of the family responsibilities and, in her remaining time, can also take care of her career.

x

Modern societies have gained a great deal from the promotion of diversity, multiple choices, and equal opportunities. When society gives women the chance to prove their abilities and triumph, the benefit is not only for women. It is also for society itself, which achieves the best use of its available potential. Excellence, both in the fields of science and in every aspect of social life, is largely related to the more meritocratic expansion of the population base that drives progress.

The inclusion of more and more women in the fields of science and technology will infuse these areas with the particular values associated with the female gender. The European framework itself has been built upon predominantly “feminine” values, such as resorting to dialogue and cooperation to solve problems and differences, forming bonds between nations based on their common interests, and seeking agreement through negotiation. These principles, which, according to Jean Monnet, serve as a counterbalance to the blunt resort to violence, are responsible for the success of the project of a United Europe. As long as we remain faithful to these values, we have greater hopes for an even better Europe.

Proposals and Policy Measures [17]

- Creation of an international information bank, in collaboration with the EU, UNESCO, and the OECD, with gender-specific data, an essential tool for developing policy for women scientists and enhancing the role of women in the EU.

- Development of comparative trans-European analyses of the achievements of women in science and the effects of social, cultural, economic, and political factors on the emerging trends.

- Creation of support groups and professional networks for women scientists.

- Promotion of measures to reduce gender inequality due to the additional workload of women scientists who provide care services:

– providing care for children and the elderly

– more flexible requirements for the completion of doctoral theses by women

– measures to create a greater degree of gender equality in the distribution of responsibilities within the family (reconciliation of private and professional life). - Evaluation of the effectiveness of existing affirmative action programs in education, science, and technology.

- Publication of manuals promoting gender balance in science and politics.

- Promotion of equal opportunities for boys and girls, through the enhancement of their interests and not categorization according to traditional expectations for each gender.

- Development of teaching methods that are female-friendly.

- School career guidance for boys and girls for a potential career in science.

- Training of trainers on gender equality issues, in order to prevent the transmission of traditional stereotypes about the two genders.

- Presentation of successful women scientists as role models in schools and the media.

- Creation of indicators to determine gender equality in the distribution of educational resources, scholarships, and research funds.

- Presentation of the rationale and benefits of women’s participation in science to politicians, the media, and decision-makers in education and science.

- Development of a new approach to science that will expand the influence of a perception of science connected to sustainable development, cultural values, gender equality, and global interest in a human society.

- Taking measures to integrate the gender dimension in the development of this new form of understanding of science.

- Promotion and dissemination of literature on gender equality in science, which incorporates gender sensitivity and challenges the androcentric perspective.

- Creation of discussion forums among scientists on gender equality issues relevant to their specific field, based on a multidisciplinary approach.

- Integration of the gender dimension into research and development programs (gender mainstreaming).

- Development of macro and micro programs that reflect the specific concerns and areas of interest of women.

- – Measures to create a greater degree of gender equality in the distribution of responsibilities within the family (reconciliation of private and professional life).

The integration of the gender dimension in the development of science and new technologies not only raises issues of access, quantitative participation, and equal representation of women, but also a profound question and critical assessment of the culture of the new society with its values, development strategies, goals, and the involvement of human resources.

Anna Karamanou

PASOK MEP

President of the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

Member of the Bureau of the Socialist Group in the European Parliament.

Table 1: Percentage of female employees and researchers in Higher Education Institutions (1999).

Source: European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 259.

Table 1: Percentage of female employees and researchers in government positions (1999).

Source: European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 259.

Notes

[1]European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 257. The statistics from previous years presented here come from national sources.

[2] European Commission Website, Women and Science, www.europa.eu.int/comm/research/science-society/women-science.

[3] European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p.259.

[4] European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 260.

[5] Anna Karamanou, The Greek Woman in Education and Employment, 1984.

[6] European Parliament, Report on Women in the New Information Society (2003/2047(INI)), Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, Rapporteur: Anna Karamanou, p. 13.

[7] European Commission, Communication from the Commission: The Role of Universities in the Knowledge Europe, Brussels, 05.02.2003, COM(2003) 58 final.

[8] European Parliament, Report on Women in the New Information Society (2003/2047(INI)), Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, Rapporteur: Anna Karamanou, p. 12.

[9] European Parliament, Report on Women in the New Information Society (2003/2047(INI)), Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, Rapporteur: Anna Karamanou, p. 13.

[10] European Parliament, Report on Women in the New Information Society (2003/2047(INI)), Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, Rapporteur: Anna Karamanou, p. 13.

[11] European Parliament, Report on Women in the New Information Society (2003/2047(INI)), Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, Rapporteur: Anna Karamanou, p. 14.

[12] www.europa.eu.int/comm/research/leaflets/science/el/page1.html.

[13] European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 267-268

[14] European Commission Website, Women and Science, www.europa.eu.int/comm/research/science-society/women-science.

[15] European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 266-267.

[16] European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 267.

[17] Enwise Workshop Balkans