Exclusive: Anna Karamanou’s interview about her landmark book in the history of Greek women – Shame on the women’s taboo at Mount Athos.

A useful and very beneficial book! Unique in its category!

In her new book The Peaceful Uprising of Female SAPIENS, Anna Karamanou takes us on a fascinating historical journey, beginning with the Revolution of 1821 and concluding with the pandemic and the MeToo movement of 2021.

It offers essential historical and political knowledge about the 200 years of the modern Greek nation-state that every Greek man and woman should be familiar with.

Major historical events, the role of political and military leadership, triumphs and national disasters, the role of women, and the ideas that shaped modern Greece are recorded in detail.

Amidst the clamor of politics and historical events, we witness the peaceful uprising of female sapiens, who, under the banner of universal values, claim their fundamental human rights and gender justice.

The book reveals the silenced feminist struggles and the significant contribution of women in the expansion and institutional foundation of the modern Greek state, from Ioannis Kapodistrias, King Otto, Charilaos Trikoupis, and Eleftherios Venizelos, to the contemporary European era.

It offers ample material for pride and tears, for reflection and self-awareness!

Read below the interview of Anna Karamano with Eirini Nikolaopoulou

Mrs. Karamano, you write that the Greek women participated in the 1821 Revolution uninvited, without conscription, and emerged from the margin and obscurity to the forefront of history—please tell us more about this.

In Greek history, there was never conscription or an obligation for women to participate in military operations. Gender roles were historically shaped by long-standing patriarchal traditions. War and conflicts exclusively belonged to men, as did the rewards for bravery and courage!

However, the uprising of 1821 and the passion for liberation from the Ottomans shattered centuries-old social stereotypes. Many women, on their own and uninvited, threw themselves into the battle, giving their fortunes and their very lives to the great struggle. There was, in fact, a challenge and overturning of the patriarchal order, initiated by the women themselves.

In the shared struggle for liberation, the equality of men and women was achieved on the battlefield.

The protagonists, Manto Mavrogenous and Bouboulina, along with thousands of other volunteers, emerged as symbols of combativeness, patriotism, and self-sacrifice, disproving the notion of the weak female nature and overturning the rules of patriarchy. Manto Mavrogenous fought side by side with Dimitrios Ypsilantis!

Can you briefly mention which small groups of pioneering women have written the history of feminist struggles in Greece over the past 200 years?

The first women to break down the walls of patriarchy, albeit temporarily and amidst war, were the pioneering fighters of the 1821 Revolution, with leading figures such as Manto Mavrogenous and Laskarina Bouboulina. Their bravery marked the beginning of subsequent feminist struggles.

However, the contribution of women to the liberation was not recognized, and they were immediately excluded from holding positions of power. Women were considered worthy in war, but not in the administration of the newly established state.

Not even the right to education and work was recognized for them. Harsh patriarchy once again took its throne and confined women to their homes under the authority of the male sapiens. The case was then taken up by the few educated women of the time, mainly teachers.

Syros was a pioneer, with the scholarly women Evanthia Kairi and Maria Aivalioti leading the way. In 1831, the Hil School began operating, followed by Zappeio and Arsakeio. Then came Kalliope Kehagia, who founded the first association called the “Ladies’ Association for Female Education” in 1872.

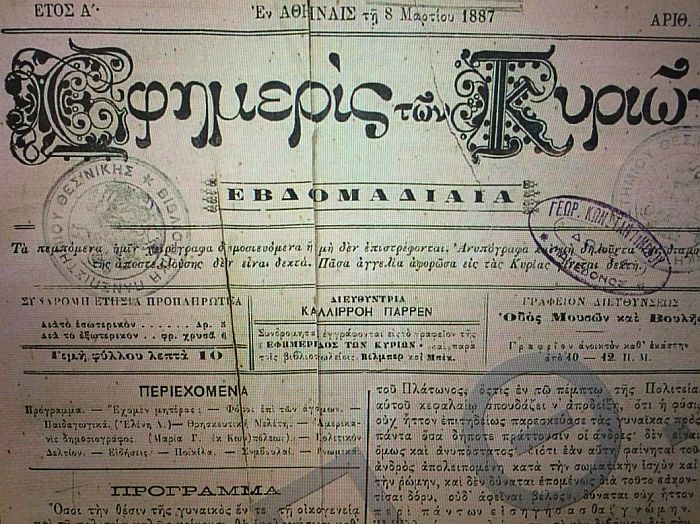

A major milestone in the history of feminist struggles was the publication of the journal “I Efhmeris ton Kyrion” (The Ladies’ Newspaper) on March 8, 1887, by the prominent feminist, journalist, and educator Kallirroi Parren (1861-1940).

It was published on March 8, 1887, and continued to be published for 30 years, marking the uprising of the “female sapiens” against the patriarchal order. It took a great deal of courage for Parren to write in the first issue that men should not have the monopoly on thinking and judging.

From the very beginning, she raised the issue of women’s participation in politics and decision-making, challenging male dominance.

“The Ladies’ Newspaper” (“Η Εφημερίς των Κυριών”), with contributors exclusively from a small circle of educated middle-class women, was published in 3,000 copies and became highly sought after. It was reprinted in 7,000 copies, which sold out the same day. Its quality was exceptional, and the contributors were highly active both in Greece and in Europe.

“The Ladies’ Newspaper” fought a hard battle for women’s education, labor rights, and the opening of higher education to women. Greek feminists were present in shaping Greek society and forging national consciousness.

In the negative atmosphere for women’s claims in post-Ottoman Greece of the 19th century, the first women’s magazines and literary works were published, and women’s organizations were founded. Among the magazines of the time, some played a significant role in spreading feminist ideas as well as in promoting national aspirations.

Others simply reproduced the social stereotypes and prevailing perceptions of the time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, many organizations were founded that continue to operate today: The National Council of Greek Women (1908), the Lyceum of Greek Women (1911), the Association for Women’s Rights (1920), the Union of Greek Women Scientists (1924), the Socialist Women’s Club, the Panhellenic Union of Women (1946), the Panhellenic Housewives Union (1951), the Soroptimist Union of Greece (1952), and the Collaborating Women’s Associations, which had united forces since 1924, consisting of the National Council of Greek Women, the Association for Women’s Rights, the Lyceum of Greek Women, XEN Greece, the Union of Greek Women Scientists, the Union of Intellectual Women, and the Greek Federation of Women’s Associations founded by Lina Tsaldaris.

In 1961, following a proposal by Maria Svoulos, the Union of Greek Women Lawyers was founded. In 1964, the Panhellenic Union of Women (PEG) was re-established, creating branches throughout Greece and advocating for equal pay for equal work.

After the fall of the junta, in 1974, the most mass-based feminist organizations were founded. A defining feature of the Greek post-junta feminist movement, beyond its massiveness, was that the demands and issues it raised had a strong political character.

Along with the new political parties, new feminist organizations emerged, the most significant of which were: the Movement of Democratic Women, founded in 1974 by women from the Left; the Women’s Union of Greece in 1976, under the dynamic presidency of Margarita Papandreou, with women affiliated with PASOK; and the Federation of Greek Women, aligned with the Communist Party of Greece (KKE).

Why do you dedicate this book mainly to the women of the new generation?

The new generation is the future of the country and the planet, but also the future of equality and gender reconciliation.

The new generation of women, the most educated in the 200 years of the Greek state, needs to learn from the example of the pioneering Greek women, who, starting in the 19th century under harsh socio-economic conditions and enduring periods of war, crises, poverty, civil wars, and political upheavals, overcame attacks, slander, and ridicule, and paved the way to achieve all that is now considered taken for granted and self-evident.

They must continue the fight for a better world, free from discrimination, inequalities, and all forms of violence.

I share your justified outrage at the fact that the names of figures like Bouboulina or Manto were never found in any official documents, institutions, or national assemblies, and that women were excluded from the universal right to vote in 1844 or 1864.

Not even the names of the female fighters were mentioned in the assemblies by the men. It was as if they never existed. The same happened with the decision for the first Assembly of 1844 and its constitutional establishment in 1864, which recognized “universal” suffrage only for male sapiens. There was no discussion whatsoever for women.

It was the first electoral law in Europe that established universal suffrage (but only for the male population). Unfortunately, the great opportunity for Greece to lead the world in granting voting rights to women was lost.

Women were ignored by all the constitutions before and after the liberation, until 1975, when the constitutional equality of Greek men and women was secured (Article 4, paragraph 2), and when, in 1983, the New Family Law left behind the Ottoman legacy.

I would like a clear and very brief answer to what you repeatedly mention in your book, that is, that Greece and its development would have been very different if half of the population, the women, who were excluded, had participated.

No country can progress if it does not fully utilize the material and intangible resources it possesses. Greece has not harnessed its female potential, and this is a major reason for its delay in many areas. It remains last in the EU’s gender equality rankings.

The results of the triple elections in 2019 confirm this (see in detail in my book). All studies and research show that gender equality is directly linked to economic and social development. Look at which countries are on the global map. In Greece, the culture of the East, along with the deep devaluation of women that characterizes it, hinders both gender equality and meritocracy.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) documents the anti-development role of discrimination and inequalities against the female workforce.

Even at the company level, data shows that the inclusion of just one woman on the board of directors or in another senior leadership position is associated with an increase in return on assets (ROA) by 7 to 8 percentage points. Is anyone listening?

What do we owe to the first Greek woman who spoke about equality, the journalist Kallirroi Parre?

She was the first and the bravest to have the courage to bring the issue of women’s rights and gender equality into the public debate in an entirely male-dominated society – at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Rights to education, higher education, employment, and politics were not yet taken for granted for women.

A rare personality, Parrén, editor of the legendary publication *I Efimeris ton Kyrion* (The Ladies’ Newspaper), educated, a fighter, affluent, and with a supportive husband, paved the way for future generations of women. We owe her a lot! Historians and politicians almost ignored her. We have not seen her name on any major street.

However, we have named the central avenue of the capital after Queen Sophia, the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and wife of King Constantine.

How would you briefly substantiate that with the contribution of women in the victorious Balkan Wars, the doubling of Greece was achieved?

Women were present at all the critical moments of modern Greek history. They made a significant contribution to the victorious Balkan Wars, which doubled the size of Greece, under the inspired leadership of Eleftherios Venizelos. The participation of women has been overlooked by historians.

However, women were present in the care of the wounded, in the transportation of supplies, in organizing food rations, and in the production of ammunition, clothing, and food.

And, of course, they took the lead on the battlefield when needed, such as during the capture of Ioannina and the liberation of Epirus, where there are significant testimonies of the bravery of women (page 197 of the book).

If we had to count on one hand the five crucial steps for Greek women to approach equality, which would you mention?

There is no need for five steps, but one decisive step: To ensure, both legally and practically, that democratic institutions and centers of political and economic power will include both men and women equally and with mathematical balance, so that they can share fairly and make joint decisions on all matters of public and private life.

The unequal distribution of power between male and female sapiens is, in my opinion, the root cause of all other inequalities, discriminations, and violence against women.

Patriarchy, of course, resists strongly and sometimes with the use of violence, in order to protect its privileges and its divinely ordained sovereign rights over female sapiens. Men perceive the demand for democratic gender equality as a zero-sum game and view with fear the modern advance of women who are taking one fortress after another.

Top academic studies (Harvard Business Review, Dec. 2020) already show that women as leaders have unique advantages compared to men. They possess greater empathy and willingness to help others, more ability to perceive risks, and greater resilience in the face of difficulties and failures.

Successful women have shattered the myth that compassion, emotion, and a humanitarian approach are disadvantages for a leader.

I will focus on the issue of the Monastic State of Mount Athos because it deeply pains me, but I could not compare myself to your struggles on this matter. We risked ridicule and terms like “quaintness” and so on, yet no real counterargument has ever been given. Correct?

Certainly, there are no arguments, nor even a theological basis, for the exclusion of the female gender from Mount Athos, with its 20 male-dominated monasteries. It is unprecedented worldwide! The Monastic State is a taboo subject for Orthodox Christians.

The symbolism that conveys the supposed superiority and sacredness of the male gender, supposedly revealed by divine will, is very powerful. It is a shameful remnant of the dark times of ignorance and superstition that, unfortunately, still survives today. Shame also on those who accept and consent to such a grave affront to the female gender.

I dedicate this book to my granddaughter.

So, to the new generation, what hurts you the most and what is it that you pass on as your vision for how you would like to see the Greek woman of 2030?

First of all, I would like my granddaughter to be happy in her life, meaning to have (good) fortune, (and may she have brilliant luck…), along with everything else: good health, good studies, love of learning, integrity of character, hard work, good interpersonal relationships, and faith in democratic principles and values.

I would like her to live well and help those around her to live better. To approach life’s problems with a humanitarian mindset and empathy.

I am concerned about the rise of cancel culture and the egocentric interpretation of things.

It is a fact that living conditions and the values that accompany them are changing at an astonishing speed. There are many new challenges and upheavals: pandemic, climate change, environmental degradation, deep inequalities between states and people, violence, waves of migration and refugees, racism, deniers of reality, and the digital revolution.

However, I believe that today’s youth, the most educated generation in history, will manage even better than my generation. They started from a better starting point of goods, science, and prosperity! The end of patriarchy that is approaching heralds a new, completely different civilization, with equality, peace, freedom, and the triumph of humanitarian values.

If you could please point out a few “catchy” phrases like the one you wrote about what Kolokotronis said to Othon.

Choices, after going through the whole book! Useful!

“Rigas Velestinlis: Schools for Male and Female Children”

The Rights of Man, Article 22: Everyone, without exception, has a duty to learn to read and write. The country must establish schools in all villages for both male and female children. From education comes prosperity, with which free nations shine.

The Declaration of the Peloponnesian Senate: schools for boys and girls.

The political text of the Struggle (27.04.1822) appealed to the Greeks not to neglect education: “Do not neglect the education of your beloved children, both boys and girls. Do not strive to leave them an inheritance of money, but gladly spend the excess money to provide them with the true and secure treasure of education…”

(Public secondary education for girls was passed in 1917)

The journalist and historian Ioannis Filimon on Bouboulina.

The national uprising found Bouboulina in her fifties, beautiful, fierce as an Amazon, and an imposing captain, before whom the coward would falter and the brave would retreat.

Governance of Ioannis Kapodistrias, 1828-1831

The report of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, A. Lontos, provides a vivid description of the chaos that prevailed when Kapodistrias took over:

In Greece, there is neither trade, nor crafts, nor industry, nor agriculture. The peasants no longer sow, because they have no belief that they will reap, and even if they do reap, they do not hope to protect their harvest from the soldiers.

The merchant is not safe in the cities; he trembles from the fear of pirates, who keep their eyes wide open, waiting to attack the ships as they pass. Murder covers theft with secrecy, and the craftsman is uncertain whether he will be paid for his work. The right of the stronger is the only thing that truly exists.

A characteristic description is also given by the German Friedrich von Tiers:

The country, as much as had been liberated by that moment, resembled a pile of ruins still smoking after a devastating fire. On land, the law of the predatory local lord, the koτζάμπασης, prevailed, and at sea, piracy reigned.

The Morea was a wreck. Every great captain who held a castle (Monemvasia, Petrobey; Acrocorinth, Kitzos Tzavellas; Palamidi, the Grivas and Stratos) tyrannized the naked and homeless population like a conqueror. There was no production, nor hands available to engage in farming due to insecurity. The population had sought refuge in the mountains and caves. There was no state, even in its most rudimentary sense…

Assassination of Kapodistrias: Assassination of the homeland

The great benefactor of Greece, Eynard, succinctly summarizes the consequences for Greece from the assassination of Kapodistrias in one sentence:

“The virtuous man… who sacrificed everything for his country, died as a victim of personal vengeance… The Greeks of all factions will later realize the immeasurable damage they suffered, they will soon see that there is no one capable of replacing the absence of Count Kapodistrias, and when they examine all that he did for his country, they will recognize him as the most virtuous man.

The death of the Governor is a disaster for Greece. It is a European tragedy, I am not afraid to say it… I say this with double sorrow, the villain who murdered Kapodistrias, murdered his own country.

Theodoros Kolokotronis later, in 1836, commented as follows on the governance of Kapodistrias: “Kapodistrias destroyed Greece because he immediately made it Western (Frankish), whereas, to begin with, he should have made it three parts Western and seven parts Turkish, then half-and-half, and later, completely Western.”

The testimony of Edmond Abu: Life under Otto.

According to Abu, men prefer to show off in the village square rather than work in the fields. They send their wives and daughters to do the work instead. Women generally live away from the other sex. Social gatherings are rare. At the village dances, women dance among themselves, and the men do the same.

In certain provinces, such as in Messolonghi for example, the fiancé enjoys the same privileges as a husband. They wait to celebrate the union when the first signs of its fruits appear. If the future groom, after enthusiastically celebrating the engagement, were to retreat in the face of the wedding mystery, his refusal would cost him his life.

They tell the story of a fiancé who ran away the day before the wedding on a Portuguese ship. He fled at the last minute to Lisbon…

Eleni Glykantzi-Arveler: Christianity, Romiosyni, and Hellenism—everything is Byzantium. It is the unbroken link between ancient Hellenism and the modern world. Byzantium, although misunderstood, bequeathed to Europe linguistic terms that are almost all related to ideologies, religion, and ecclesiastical practice.

Elena Venizelou: I never went to school.

In the 19th century, girls moved from their parental home to their husband’s house…I never went to school, I have no idea about cooking or gardening. With tutors who came to the house, I learned languages and speak many fluently. They taught me geography, history, literature, and music.

The “Emancipation” of Georgios Souris (1901) provoked much laughter, especially when the scene showed the hero abandoned by his “emancipated” wife, struggling alone to manage with the child.

Our emancipation, although it may lack formalities, has essentially been achieved—nothing is missing: smoking, uprooting, running here and there to cafés, bicycles, politics, independent living, and the promise of progress. Stock exchange, clubs, baccarat, the fruits of science, registration and attendance at the university, perhaps to find husbands who honor education.

Who is Who

Member of the European Parliament (1997-2004), member of the Bureau of the Socialist Group, and president of the Parliamentary Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality.

Vice-President of Women of the Party of European Socialists and Democrats (PES) since 2004.

Social and international politics, lifelong learning, gender equality, political philosophy, and human rights are at the core of her interests and actions.

Unionist of OTE (1974-1991), General Secretary of the OTE Workers’ Federation, member of the Women’s Committee of GSEE, member of the Women’s Committee of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), representative of GSEE in the Board of Directors of OAED.

Founding member and General Secretary of the Political Women’s Association, member of the Association of Greek Women Scientists and the Hellenic Political Science Association.

National representative in two European networks of the European Commission (1982-89 & 1992-96), on equal opportunities and employment policy, secretary of the Women’s Sector of PASOK (1994-2001), vice-president of the Socialist Women’s International (1996-2003), Secretary General for Equality of the Ministry of Interior (1996-97).

“Peace and Friendship A. Ipekci” Award for contribution to Greek-Turkish rapprochement (1999), Soroptimist Union Prize (2004), and International Award from the Hungarian Government (2008) for contribution to the struggles for women’s rights.

Studies: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens:

a) Bachelor’s degree in Greek and English Philology from the Faculty of Philosophy, 1978

b) Master’s degree (with distinction) in European and International Studies, 2006

c) PhD in Political Science and Public Administration (with distinction), 2014

Many articles and essays in Greek and European publications, scientific journals and books.