Multiculturalism or pluralism?

The waves of refugees and the humanitarian crisis accompanying them, terrorist attacks, the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, and the dispute over the hijab, once again bring to the heart of public discourse the issues of multiculturalism, pluralism, identity, security, culture, diversity, social cohesion, and the peaceful coexistence of people with different values and ways of life. Throughout the historical course of humanity, we encounter large population movements, particularly after World War II and more intensively after the end of the Cold War. During this period, the rapid political, economic, and techno-scientific changes taking place undermine the homogeneous nation-state and highlight many deterritorialized national and multinational collectivities. According to Jürgen Habermas, we live in a “post-national constellation,” in a globalized society with international centers of power and with multiethnic and multicultural characteristics [1].

“Permanent peace” is still far off, as the economic crisis, blind terrorist attacks, and violence seem endless.

Many intellectuals and political analysts wonder if we are moving from the Westphalian state towards the Kantian ideal of cosmopolitanism, as outlined in his monumental work “Perpetual Peace,” meaning a transition from international law between independent states to a global, cosmopolitan law [2]. Kant’s dream, through the United Nations, the European Union, and other regional unions, may have started to take shape. The world now seems to function more as a unified whole, rather than as disconnected state entities. Undoubtedly, the interdependence of states and the global dimension of politics have gained greater significance in recent decades. The United Nations Declaration recognizes individuals as bearers of rights that, in some way, transcend the established norms of sovereign states. Similar developments can be seen with the Court of Justice of the European Communities, the European Court of Human Rights, and the International Criminal Court in The Hague. In all of these cases, individuals whose rights are violated can resort to international courts, bypassing the nation-state. Even the activism of numerous international non-governmental organizations, as seen with the refugee crisis in Greece, creates new dynamics. However, “Perpetual Peace” is still far from coming, as the economic crisis, wars, migration and refugee flows, the blind terrorist attacks of jihadists, and violence seem to have no end.

In Greece, as in other European countries, the sudden transition from societies with relative linguistic, ethnic, and religious homogeneity to multilingual and multicultural societies has caused significant reactions. Those who feel threatened by the changes view the new reality with distrust and fear, while ethnocentric and xenophobic political rhetoric finds fertile ground. Far-right parties claim that the European Union is at risk of Islamization, due to demographic trends—the rapid shrinking of the EU population and the swift expansion of the Islamic world. Conspiracy theories about dark plans for Islamization, through the promotion of migration flows to Europe, are currently thriving. However, the idea of European integration is based on racial, ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity, as well as the free movement of people and goods. The collapse of the ideological foundations of racism and the horrors of war led the peoples of Europe to realize that prosperity and progress can only be achieved through harmonious coexistence, social justice, solidarity, and cooperation among people. From its early steps, the European Union prioritized the protection of human rights and the fight against all forms of discrimination (European Convention on Human Rights-1950).

The public dialogue

The honorary chief of the Hellenic Army General Staff, Frangoulis Frangos, argues that it is realistic to estimate that “if this handling of the migration issue continues, then the gradual Islamization of Greece is simply a matter of time” (Kathimerini, 21.02.16). From a different perspective, Professor Panagiotis Ioakeimidis, in response to the threat of Islamization, has proposed the “Europeanization” of Islam and its enrichment with basic democratic values, “to the extent that this is possible” [3]. The UNESCO Universal Declaration of 2 November 2001 supports that multiculturalism is the common heritage of humanity and is as necessary for the human species as biodiversity is for nature (Article 1).[4]However, many questions arise. How peaceful can coexistence be when different communities have different forms of rationality, knowledge, and moral codes? How can “the other” and their system of values be accepted when they conflict with universally accepted human rights, gender equality, and fundamental freedoms? Can cultural traditions outweigh human rights and the imperatives of the rule of law? Can there be a balance between human rights and tolerance of practices that blatantly violate them? Ultimately, can the universal values of European Enlightenment, based on reason, be unconditionally accepted by all cultures, or should we accept the cultural relativism of postmodernism, reinforcing each particular culture and the preservation of the cultural identity of each distinct group, within the framework of multiculturalism?[5]

Can the universal values of the European Enlightenment be accepted by all cultures?

The term multiculturalism refers to the coexistence in a given geographic area of multiple cultural differences, primarily based on ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity. Cultural diversity is also expressed through systems of values, lifestyle and living standards, social organization and behavior, dress codes, art and literature, as well as philosophical worldviews. Multiculturalism, therefore, refers to fundamental changes in the structure of society influenced by the coexistence of groups with different cultural traditions, values, and ways of life. Pluralism refers to liberal democracy, Karl Popper’s “open society,” tolerance, and the variety of views, without being synonymous with multiculturalism. [6]

The public debate on multiculturalism has proven to be very difficult. Intellectuals such as Brenna Bhandar [7], Soti Triantafyllou [8], and Giovanni Sartori [9] argue in favor of pluralism, rather than multiculturalism. [10]Professor P. Kitromilidis (Kathimerini, 31.01.10) writes that for multicultural solutions to work, certain prerequisites must be met to make the endeavor sustainable. The existence of social coexistence rules is paramount so that societies can avoid mass forms of unlawful behavior. An equally necessary prerequisite is the existence of education, primarily based on the cultivation of language and cultural heritage, so that multiculturalism does not devolve into a social and moral Babylon, but instead becomes a conduit for social cohesion. [11] Kostas Papachristos, a school counselor, argues that a dialogue of cultures can exist and a common ground can be created through a dialectical process, in which all sides are willing to subject their views to critique, dialogue, and revision.[12]

Women are coerced into choosing between “rights” and “religion.” The “choice” is impossible.

Others, usually former leftists, advocate for respecting multicultural claims for flexibility and respect for any form of difference, accusing those who express reservations of racism or cultural imperialism. However, they often appear indifferent to what happens within minority cultural groups. Attacks are mainly directed at feminists, who place gender equality above the rights and demands of many immigrant groups for autonomy. It is worth noting that initially, the feminist pursuit of gender equality and respect for diversity was thought to coincide with the goals of multiculturalism. Today, however, the view that women’s demands undermine cultural diversity is supported by many “progressives.” Women are often coerced into choosing between liberal democracy and the cultural community, between “equality” and “culture,” or between “rights” and “religion.” For many women, this “choice” is impossible. Women wish to be able to choose both. (M. Sander, 2007). [13]

In recent decades, especially after the end of the Cold War, discussions and theoretical inquiries regarding difference, tolerance, and multiculturalism have forced many Western countries to develop multicultural policies that recognize and protect cultural diversity, particularly minority cultures operating within majority cultures. In many cases, this has led to exemptions from laws or the granting of “special rights” where deemed necessary to prevent the disappearance of the specific culture.

Will Kymlicka, in his book *Multicultural Citizenship* (1995), discusses the theory of applied liberal thought for minorities. While maintaining the core principles of political liberalism regarding autonomy, he supports the sociological argument that every individuality needs roots, meaning community, culture, and history.[14] For this reason, Kymlicka defends “national” cultures as sources of liberalism. He proposes a “liberal multiculturalism,” known as the culturalist consensus. These positions, along with those regarding geographic minorities in Central and Eastern Europe, were considered by many as dangerous for secessionist movements. However, Kymlicka’s theoretical work aims to strike a balance between the cultural rights of minorities and the need for the creation of nation-states that would embrace minorities. [15]This position is countered by those who oppose “racial politics,” which undermine liberal values and human rights. An attack against the “multicultural consensus” and Kymlicka’s theory was launched by Brian Barry with his work *Culture and Equality*.[16] and the feminist political philosophy professor Susan Moller Okin.

Multiculturalism and Gender Equality

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) by the United Nations, along with many subsequent declarations, generally referred to human beings without distinguishing between genders, without acknowledging that some rights were treated differently for women. At that time, there was hardly any country in the world that did not have laws discriminating against women, often concerning fundamental rights and freedoms. In many European countries, women were not even granted the right to vote (in France in 1944, in Greece in 1952, in Switzerland in 1971). Today, however, many changes have occurred in the lives of women, thanks to gender equality policies promoted by the European Community, but the distance to full and substantial equality remains vast. Unfortunately, gender inequality, even within the European Union, is still often seen as more natural and inevitable than other forms of discrimination, such as race, national origin, religion, or political beliefs, while culture is often used as a justification for the unequal treatment of women.

Gender inequality is viewed as natural and inevitable.

The first human rights declaration, with a reference to women’s rights and without neutral language, was the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women” (CEDAW, 1979). This Convention, during its ratification process, faced more objections from governments than any other, with the justification that many of the rights it proclaimed were incompatible with the cultures and religions of their countries. However, the mobilization of feminist organizations at the international level led to the recognition of women’s rights as human rights at the Vienna World Conference on Human Rights in 1993. In September 1995, at the UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, further progress was made, despite opposition from the Vatican and radical Islamists. Both CEDAW and the Beijing Platform for Action acknowledge respect for cultural rights and religions, but also emphasize that “full gender equality may require changes in culture.”

The relationship between feminism and multiculturalism has been thoroughly examined by the prominent political philosopher Susan Moller Okin. Her 1997 essay, titled “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?”, sparked a storm of criticism and debates.[17] Okin poses the following question: What should be done when the demands of minority cultural and religious groups conflict with the principle of gender equality, which, at least officially, is recognized and applied by liberal democracies? Okin explains that women should not be discriminated against because of their gender, that they should be recognized as human beings with equal dignity to men, and that they have the right to live fully and freely, just as men do. It would be impossible to disagree with this stance. The problem is that various cultural groups living in democratic regimes believe that their rights are not adequately protected through the guarantees of individual rights and, therefore, should be protected by granting these groups special rights and privileges.

140 million women have undergone genital mutilation.

Liberal democracies must certainly protect the individual rights of all women within their borders, including women whose cultures and religions punish them by denying them fundamental rights. However, based on which logic and humanitarian values should they recognize special rights or privileges for minorities that would help them maintain their hostile-to-women culture in a foreign country, as many multicultural theorists suggest? The special treatment sought by most multicultural groups mainly concerns gender inequalities and human rights violations, such as: forced marriages, child marriages, divorce systems to the detriment of women, polygamy, sexual mutilation, double standards of moral behavior, honor crimes, head covering, and restrictions on free movement.

The World Health Organization estimates that 140 million women worldwide have undergone genital mutilation, while two million are exposed to these practices every year. According to UNICEF, every day 6,000 girls between the ages of 4 and 10 are subjected to mutilation, although the practice varies greatly from country to country. Tragically, at least half of the African countries that observe this “tradition” have adopted legislation that fully or partially prohibits it or have committed to it through the Cotonou Agreement with the European Union, yet the law is not respected. [18]Clearly, prejudices and social traditions have more power than laws. In Europe, there are valid concerns that these criminal practices have been carried over to the Union countries along with immigration flows. The European Parliament estimates that 500,000 women and girls living in Europe suffer from the long-term consequences of female genital mutilation, while an additional 180,000 are at risk each year.[19]According to data from the Health and Social Care Information Centre in the UK, by September 2014, 4,989 cases of female genital mutilation had been recorded at the national level (Guardian, 23.09.2015). However, among the EU countries, only the UK, France, and Sweden have legislation that punishes this horrific practice, though legislation alone cannot eliminate it.

In the case of France, the right to polygamy was considered a minority right, unavailable to the rest of the population. It is estimated that 150,000-400,000 polygamous families live in France, despite the fact that polygamy has been banned since 1993. Polygamy hinders gender equality as well as the social integration of migrants. For this reason, the French government has deployed social workers to persuade second and third wives to move with their children to separate apartments. The effectiveness of these measures is questionable. The case of polygamy is a very characteristic example of the deep conflict and increasing tension between feminism and the effort to protect cultural diversity. [20]The European Women’s Lobby has highlighted the danger that “religions refuse to question patriarchal cultures that promote the ideal role of wife, mother, and housewife, and refuse to adopt positive measures for equality.” The EWL strongly criticizes the fact that religion is often used as an excuse for attacks and violations against women.[21].

According to Susan Moller Okin, many feminists, especially those who are politically progressive and oppose all forms of oppression, have overestimated the ability of feminism and multiculturalism to reconcile. On the contrary, Okin emphasizes that the conflict between the two theories is expected to intensify as multicultural action focuses on securing rights for minority groups without considering whether these groups respect fundamental human rights or gender equality. She argues that cultures or religions that violate human dignity and women’s rights do not deserve to be preserved or protected. [22] Against Moller Okin, Homi Bhabba (1999) wrote, arguing that Okin looks down on “non-Western” peoples.[23] On the other hand, Martha Nussbaum (1999), commenting on Okin’s essay, affirms that the focus on multiculturalism hides great risks for women’s rights and gender equality.[24]The Vice-Rector of the University of the Aegean, Chryssi Vitzilaki, in her book *Gender and Culture* (2006), observes that, while over the last 150 years there have been significant analyses concerning the class content of culture, gender as an analytical category was systematically silenced until recently.

In Greece, a very characteristic example is that of Thrace, where the Islamic law, Sharia, applies to Muslims instead of the laws of the Greek state (Law 1920/1991), while it was abolished in Turkey in 1924. On May 23, 2010, Dora Bakoyannis, on the occasion of the visit of the Turkish Prime Minister, called for the abolition of the application of Islamic law in Thrace, describing this reality as a national disgrace, which unfortunately no government, including the New Democracy government, has decided to eliminate. “Today, Greece,” emphasized the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, “is the only European country that applies Sharia to its Muslim citizens, deviating from the Civil Code in matters of marriage, divorce, guardianship, custody, wills, and inheritance.”

Only in hardline Islamic regimes, such as Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan, does this system survive. The result is that children are married off through intermediaries at the age of 14, the right to divorce is not recognized for women, and mothers are forced to lose custody of their minor children.

Justice, multiculturalism & “group rights”

Unfortunately, due to a distorted view of multiculturalism, in other EU countries, besides France and Greece, deviations from national legislation apply. In an article by British social-democratic journalist and author Johann Hari (The Independent, 30.04.07), he criticizes women’s organizations for their indifference to what is happening in the closed groups of various cultural minorities, as well as for what the courts decide based on “political correctness” regarding the respect for multicultural groups. The question he raises is: “Do you believe in women’s rights or multiculturalism?” A series of decisions by German courts clearly show that you cannot support both. You must choose. The cases he mentions are shocking. One of them: Nishal, a 26-year-old Moroccan immigrant in Germany, with two children, had a psychotic husband who beat her violently from the first day of their marriage. Covered in wounds, she went to the police, who ordered the husband to leave. He refused and terrorized her with death threats. Nishal filed for divorce, hoping this would save her from the abusive husband. A judge who believed in women’s rights and gender equality would have easily ruled and decided: you are free from this man, the marriage is dissolved. However, Judge Christa Datz-Winter followed the multicultural logic. She said she could not give a quick divorce because, despite the police’s written confirmation of extreme violence and threats to her life, there was no “unjustified abuse.” Why? Because, as a Muslim woman, “she should have expected it,” the judge explained, even reading excerpts from the Quran to show that Muslim husbands have the right to use physical violence as punishment. “Look at Surah 4, verse 34,” she said to Nishal, “where the Quran says he can beat you. This is your culture.”!!

Muslim women have been reduced to third-class citizens, stripped of basic legal rights and protection.

The German magazine Der Spiegel has published a long list of horrific “multicultural” decisions by German courts. One example among many: A Turkish-German man who strangled his wife Zeynep in Frankfurt was sentenced to the lightest penalty because, according to the judge, the murdered woman had insulted his “male honor,” which stemmed from Eastern moral beliefs. Today in Germany, as well as in other European countries, Muslim women have been reduced to third-class citizens, stripped of basic legal rights and protection. This is because the doctrine of multiculturalism demands that society be divided into separate cultures, with different rules according to national origin (The Independent, 30.04.07).

Among the multicultural groups that receive special treatment from the justice system, even for common criminal offenses, are non-Muslims from East Asia, including Chinese, Indians, Japanese, and Romani. The Chinese, for the most part, believe that men are more suitable for political leadership, despite the fact that the party’s line for many decades emphasized gender equality and Mao Zedong declared that women are “half the sky.” In practice, Chinese women occupy very few leadership positions and suffer severe violations of their human rights. Similarly, the situation for Indian women is marked by violence and forced prostitution. Susan Moller Okin mentions two cases of preferential treatment due to culture by the courts: A Chinese immigrant in New York beat his wife to death for committing adultery, while a Japanese woman in California drowned her children and attempted suicide because her husband’s infidelity had dishonored the family. Both cases were judged leniently due to cultural considerations. The worst of all is that those brave activists and feminists who opposed these multicultural practices, such as British Labour MP Ann Cryer, have been stigmatized as racists. [25]Unfortunately, very often the issue is exploited by the far right, which lumps together “mass immigration and multiculturalism.”

From the perspective of Greece, there was a significant intervention at the UN by the Maragkopoulos Foundation for Human Rights, the International Alliance of Women, and the Greek Council for Refugees, at the United Nations Committee on the Status of Women, during its 54th session on March 1-12, 2010, in New York. An amendment was submitted to the text on the implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995 – UN World Conference on Women), which calls on member states “to eliminate any conflict that may arise between the rights of women and the harmful consequences of certain traditional and customary practices.”

Modern Western thought on justice has been influenced by the ideas of John Rawls, who, through his monumental first book, *A Theory of Justice* (1971), attempted to provide solutions by proposing the concept of overlapping consensus. Rawls argues that the most reliable principles of justice are those on which everyone can agree that they are fair, and that pluralism and consensus form the essence of liberal democratic thought. In any society, it is likely that a set of values can be found that people with different views on what is good can accept. This can serve as the foundation for a way of coexistence among different people.

The red cultural line of Islam.

All religions, especially Islam, which concerns us more at this time, express patriarchal views that certainly influence the formation of culture and women’s rights. Bernard Lewis, considered the foremost historian of the Middle East, identifies the greatest difference and conflict between Judeo-Christian and Muslim societies on the issue of women. [26]In essence, Samuel Huntington, regarding the clash of civilizations he predicted, was partly right, despite the fact that his theory completely ignored issues of gender and sexual liberation.[27] In reality, the cultural red line that separates the West from the Muslim world is not about democracy, but about gender equality and women’s rights. Lewis, in an interview, stated that Western visitors to Muslim countries are horrified by the subjugation and mistreatment of women, while similarly, Muslim visitors to the Christian world are shocked and appalled by the looseness of morals and what they perceive as the “irrationality” of Western women. [28]

The application of inhumane, violent, and humiliating punishments for women is a common practice in the name of religious traditions.

The mandatory covering of women’s bodies is one of the most debated requirements of Islamic law. God Himself, through the Quran, provides clear instructions (Chapter 33, Verse 59):

“O Prophet, tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to bring down over themselves part of their outer garments. That is more suitable that they will be known and not be abused.” (Quran 33:59) [29].

This isolation, anonymity, and separation of women from men are further reinforced by many other instructions in the Quran. As it has been written, the Prophet, shortly before his death, had warned « After my departure, the greatest danger for my people will come from women. They cause turmoil and are responsible for corruption and degeneration» “Men, therefore, must counter this threat by obliging women to cover their bodies and remain confined to the home.”[30]

“Islam asserts that gender inequality is God’s command, expressed through the Prophet’s sacred texts. In most Islamic countries, with few exceptions, the Quran’s instructions—disadvantageous to women—have been incorporated into legislation, including family, civil, criminal, and labor laws, thereby depriving millions of women of fundamental freedoms and basic human rights. The Quran itself, that is, God (according to Islam), through the Prophet, affirms the superiority of men and their right to beat disobedient wives (Chapter 4, Verse 34):”

Men are superior to women due to the special status granted to them by God over women, and also because men provide a dowry to women from their own wealth. Virtuous women are faithful and obedient, carefully guarding, in their husbands’ absence, what God has commanded them to preserve untouched. As for those from whom you fear disobedience, admonish them, separate them from your bed, and beat them. However, if they obey, treat them kindly. The Lord is supreme and great.

In many Muslim societies, the discussion on human rights does not include women’s rights, which are systematically violated. One of the most common crimes is the so-called “honor killings.” It is estimated that around 5,000 women and girls are murdered each year by male family members. The implementation of inhumane, violent, and humiliating punishments for women, such as flogging and stoning, is common practice in many countries under the guise of religious traditions, which are misinterpreted as “divine in nature and origin.” Perpetrators are usually unpunished, as such violence is considered an acceptable way of controlling women’s behavior and not a serious crime. In these societies, the patriarchal family structure places women under the absolute control of male family members. Female children become victims of discrimination from birth, as they are seen as bad luck for the family, unlike the birth of male children, who are considered a “gift from God.”

Of course, various apologists of Islam—in both the West and the East—continuously claim that Islam is not responsible for what happens to women, asserting that true Islam advocates equality and peace, and that tradition and social practices are to blame. They even refer to specific chapters of the Quran to support this view. If this were truly the case, then it is reasonable to question how, for so many centuries, Islam, while controlling every aspect of Muslim society—from sexual relations to diet—has not managed to eliminate inequalities and injustices against 50% of its followers. The reality shows that the most emancipated women in the Muslim world have gained rights not through religion, but through the principles of democracy and the rule of law.

The political controversy over the veil

Every day, we witness tensions and rivalries related to religious and ethnopolitical differences. Especially after the terrorist attacks by the “Islamic State,” the rhetoric of a “clash of civilizations” and a “global civil war” between the forces of political Islam and Western liberal democracies has resurfaced more strongly. The antagonism between Islam and the West has replaced the rhetoric of the Cold War. [31] Especially, women’s bodies have become the symbolic battleground of this confrontation. Under the pressure of migration flows and the refugee crisis, the destabilization of identities leads to the resurgence of traditions. Certainly, the most discussed resurgence, which continues to dominate public discourse in Europe, is the Muslim hijab. In Greece, the debate was reignited with the participation of a hijab-wearing student in the parade during the national holiday of March 25, 2016.

The rivalry between Islam and the West has replaced the rhetoric of the Cold War.

In Voltaire’s, Diderot’s, and Montesquieu’s France, which regards the secularism of the state as one of the great achievements of the French Republic, the sight of women wearing hijabs in schools, and the emerging trend of a reactionary return to the roots, has caused great tension, concern, and reflection for many years. This is why radical decisions were made to protect the educational system from religious fanatics and to keep schools free from religion. On February 10, 2004, the French National Assembly passed a law banning the hijab and other religious symbols in public schools with 494 votes in favor and 36 against, despite strong protests and criticism that the measure limits religious freedoms. The Committee, led by its chairman Bernard Stasi, the French Ombudsman, had presented the issue of the hijab to the President of the French Republic as part of the political threat Islam posed to the values of the secular state. [32]In contrast to France, in Iran, the hijab is mandatory by law.

The hijab can only symbolize the submission of women to patriarchal norms. Those in power have interpreted Islam according to their own will, always with the goal of ensuring blind obedience from women and controlling their sexuality. From the Muslim neighborhoods of France, horrific stories of women who endure persecution, rape, and torture for “missteps,” such as rejecting the Islamic hijab, occasionally come to light. However, the fact that 39% of French Muslims supported the decision to ban religious symbols, while the majority condemns the terrorist actions of jihadists, shows that a critical mass of Muslims is emancipating, liberating themselves, and preparing to join the European system of values.

In Belgium, on April 29, 2010, 136 out of 138 members of the Belgian Parliament voted in favor of a law that bans the wearing of face-covering veils across the country. The law, which does not specifically mention the burqa or niqab, states that individuals who appear in public spaces “with their face partially or completely covered and wearing clothes designed in such a way that the individual is not recognizable” will be punished with a fine or imprisonment for one to seven days. However, exceptions are made for costumes worn during carnival season. [33].

A similar stance and concern prevail in the UK, Denmark, Italy, Spain, Austria, and the Netherlands. In the UK, in October 2006, then Foreign Secretary Jack Straw asked women visiting his office to remove their niqab. These women were numerous, as Jack Straw was elected in Blackburn, where 25-30% of the population is Muslim. In his statements, he emphasized that in a Western society, where facial expressions are crucial for human communication, the Islamic veil creates separation and “parallel communities.” The incident is also well-known of the teacher who was dismissed for wanting to teach primary school children while wearing a niqab. [34].

What exactly do the young women who are wearing the hijab again aim for?

The reaction to the hijab ban has been expressed by representatives of Muslim organizations, socialists from the Council of Europe, as well as groups and human rights monitoring organizations, emphasizing that such a ban contradicts the European Convention on Human Rights. Women’s organizations are divided. In France, while members of the feminist organization Ni Putes Soumises celebrated the ban, organizations like the “Federation of Parents-Teachers,” “SOS Racism,” and “A School for All” argued that women’s rights to education and religion were being violated. Several organizations outside of France, including Human Rights Watch, The Islamic Human Rights Commission, and Muslim Women Lawyers for Human Rights, agreed. The phenomenon of the return of the hijab cannot be explained solely in religious terms. There are many questions. What exactly do the young women, primarily, who are wearing the hijab again, aim for? Obedience and submission to religion, defense and promotion of their distinct culture, veiled hostility towards Western values, an attempt to attract attention, or simple narcissism? It is not hard to answer that it is all of these motives combined. [35]

The Islamic political plan for the “purification” of the West has its roots in 1920s Egypt. In 1924, a reformist government inaugurated a modern university that allowed women to attend. At the same time, Huda Sha’arawi, Egypt’s first feminist, publicly removed her hijab, and photos of her uncovered face were published on the front pages of all newspapers. It was then that Sayyid Qutb and others founded the first Islamist group, the Muslim Brotherhood. However, Islamism matured and began to gain mass followers in the 1970s, precisely when the feminist movement started gaining political power in Europe and America, and strengthening in the urban centers of less developed countries. [36]

The creation of a common global space of freedom, peace, security, and justice is the challenge of the 21st century.

The Moroccan sociologist Fatima Mernissi (1987) argues that “what enrages fanatic Islamists is that the post-colonial era of independence did not create an exclusively male new order, as women participate in public events.” Even today, in the 21st century, many urbanized and educated men consider modern women with degrees and careers as the worst traitors to Islam. These zealots, Mernissi argues, see insults to the “true” Islam everywhere, but according to their standards, the worst heretics are the “uncovered” women.[37]Many of this generation, however, form today’s radical clerics who promote their own interpretations of Islamic law (sharia) and encourage holy war (jihad) as an obligation of faith. However, it must be emphasized that violence is not addressed with even more violence. Its causes, beyond cultural differences, should be sought in the deep economic inequalities and divisions of the modern world and in the backwardness of Muslim countries compared to the West. The creation of a common global space of freedom, peace, security, development, solidarity, and justice is the greatest challenge of the 21st century.

Conclusions

- The answers to the questions raised initially remain open. This article cannot replace extensive discussions, academic studies, and theoretical inquiries. In the new globalized environment, critical reflection needs to continue in essence, with the goal of a renewed, modern social contract and a political vision for the society of the future that will inspire, delight, and mobilize people.

- A society united in its diversity is desirable. It is widely accepted that pluralism is a source of wealth for modern open societies. However, this observation must be accompanied by the acknowledgment that it also entails costs and negative aspects. Experience has shown that there can be no social progress and economic development without modernization and progress in the realm of ideas and culture. Therefore, any attempts to renew the social contract strictly within economic and technological frameworks, while keeping the foundations of outdated patriarchal societies intact, are doomed to fail. The processes of women’s emancipation and gender equality are directly linked to the historical evolution of humanity and progress.

- The European Union has already established a common framework of rights and obligations, a modern social contract for everyone in the EU, regardless of nationality or origin. The Charter of Fundamental Rights provides the framework within which we can effectively and decisively resolve cultural or religious differences, respecting the freedom and equality of men and women. The central role of human rights and gender equality in the Treaty of Lisbon is demonstrated by their inclusion in Article 2, where the values upon which the Union is organized and operates are outlined.

- Certainly, we need a policy that prevents the disappearance of cultures while simultaneously securing the individual rights of those who participate in and contribute to culture. Feminism and multiculturalism share some common goals, such as equal rights for all people. However, cultural sensitivity alone is not enough. We need to consider the practical aspects of culture, the functioning of the system that supports it, and examine whether it operates fairly for both genders.

- It is an undeniable necessity to politically address religious fanaticism, of which women have been and remain its primary victims, and to take measures. The human rights of women, which are protected by international treaties and conventions, cannot be violated under the guise of religious interpretations, cultural traditions, customs, or legislation. No religion, no tradition, and no doctrine can stand above human rights and fundamental freedoms.

- European feminist organizations, through the European Women’s Lobby, call on governments to honor their signatures and commitments to implement the Beijing Platform for Action and particularly the “UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.” They emphasize that “the EWL does not, under any circumstances, accept arguments of cultural relativism when it comes to women’s rights, claiming that violations are dictated by faith and culture and therefore should be exempt from human rights.”

- The perspectives of Rawls, Susan Moller Okin, Sartori, Karl Popper, and Sotiris Triantafyllou are highly valuable for understanding the contemporary issues of multiculturalism. Dialogue is important because it enables people from different cultures to collaboratively address issues of mutual interest. The argument that “cultural differences must be respected” is not a justification in itself. The dialogue and coexistence of cultures must go beyond the stereotype of “respecting cultural differences” and subject all existing cultural traditions to reflective criticism, recognizing that no culture has a monopoly on good ideas, nor is any culture beyond critique.

- Revisions and profound changes are needed in our value systems, on which modern Western civilization has been built—a civilization that deifies material wealth and reproduces or tolerates discrimination, inequalities, social Darwinism, racism, and violence. Respect for human rights, without any discrimination based on gender, race, national or social origin, religion, age, or sexual orientation, is a fundamental condition for peaceful coexistence, combating violence, and fostering economic, social, and cultural progress.

[1] An. Panagidis, An. (2004), “The Imperatives of Multiculturalism in Modern Citizenship and the Role of Intercultural Education,” Speech at the Symposium “Which Active Citizen in Which Democratic Society,” Pancyprian Peace Council, 24.12.2004. See Jurgen Habermas, *The Postnational Constellation*, 2003, Polis Editions.

[2] Richard Wolin, (2010), “The Idea of Cosmopolitanism: from Kant to the Iraq War and beyond,” History Program, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, NY, USA.

[3] Panag. Ioakeimidis, (2004), “Islamization or perhaps Europeanization?” newspaper. Ta Nea, 15.10.04

[4] UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, Παρίσι, 2 Νοεμβρίου 2001

[5] A. Chatzis, 2007, “Are there limits to multiculturalism?”

(Speech organized by the Liberal Alliance on 12/5/2007 – streaming audio)

[6] The foundation of the concept of the Open Society draws its logic and arguments from the epistemological views of Popper (1902-1994). It was established in the decades of the 1930s-1950s.

[7] Brenda Bhandar Bh., (2006), “Beyond Pluralism: contesting multiculturalism through the recognition of plurality” Workshop Report, The School of Law, King’s College London, 17.11.06

[8] See Soti Triantafyllou, 2014, Pluralism, Multiculturalism, Integration, Assimilation, Pataki Publications.

[9] Giovanni Sartori, 2015, Democracy in 30 Lessons, Melani Publications.

[10] Brenda Bhandar Bh., (2006), “Beyond Pluralism: contesting multiculturalism through the recognition of plurality” Workshop Report, The School of Law, King’s College London, 17.11.06

[11] Pascalis Kitromilides, P. (2010), “National Identity as a Dilemma and a Perspective,” Kathimerini, 31.01.10. Pascalis Kitromilides is a professor of political science at the University of Athens.

[12] Kostas Papachristos, (2007) “The Dialectical Process in Intercultural Dialogue: an Alternative Proposal Based on Constructivism,” in

“Gender and Interculturalism in the All-Day Primary School” Scientific Step, vol. 6, March 2007

[13] Mudhavi Sunder (2006), “the New Enlightenment: How Muslim Women are Bringing Religion and Culture out of the Dark Ages”, Workshop Report, The School of Law, King’s College London, 17.11.06

[14] Will Kymlicka, (1995) Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[15] W.Kymlicka, (1989) Liberalism, Community and Culture, Oxford: Clarendon

[16] Brian Barry, (2000), Culture and Equality: An Egalitarian Critique of Multiculturalism, Polity

[17] Susan Moller-Okin, (1999) “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?”, originally published in Boston Review, Oct.-Nov 1997

[18] See Agreement 2000/483/EC on the partnership between the members of the group of African, Caribbean, and Pacific states and the European Community, signed in Cotonou on June 23, 2000.

[19]European Parliament (2014), Resolution of 6 February 2014 on the Commission communication entitled ‘Towards the elimination of female genital mutilation’ (2014/2511(RSP)

[20] See Anna Karamano, 2011, article “MULTICULTURALISM, HUMAN RIGHTS & GENDER EQUALITY,” in the collective volume, Interculturalism and Religion in Europe, after the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty, Indiktos Publications, pp. 209-238.

[21] European Women’s Lobby, (2006), “Religion and Women’s Human Rights”, Position paper, adopted 27.05.06

[22] Berkowitz Peter, 1999, “Feminism vs Multiculturalism?”, The Weekly Standard

[23] Bhaba, H.K. (1999) “Liberlism’s Sacred Cow”, pp 79-84, in Susan Moller Okin Is Multuculturalism Bad for Women? ed. Joshua Coen, Mathew Howard and Martha C. Nussbaum, Princeton University Press

[24] Martha Nussbaum, (1999), “A Plea for Difficulty”, pp 105-14, in Susan Moller Okin, “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?” ed. Joshua Coen, Mathew Howard and Martha C. Nussbaum, Princeton University Press

[25] Ann Cryer, Labour MP from 1994 to 2010. She fought against honor-based crimes and forced marriages.

[26] Bernard Lewis , (2004), The Crisis of Islam, Phoenix, London

[27] Βλ. Inglehart R. & Pippa Norris, (2003), “The True Clash of Civilizations”, Foreign Policy, March/April 2003

[28] Weiner Lauren, “Islam and Women-Choosing the Veil and other paradoxes”, Policy review, October-November 2004

[29] The Holy Quran, 2002, Kaktos Publishing.

[30]Christos Chalasias, (2001), Political Islam, Domios Publishing, pp. 45-49.

[31] Seyla Benhabib, (2010), “The Return of Political Theology”, Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol. 36 nos 3-4, pp 451-471

[32]‘Laïcité et égalité, leviers de l’émancipation’ by Henri Peña-Ruiz, Le Monde diplomatique, February 2004, page 9

[33] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13038095

[34] Hatzis Ar., 24.5.2007, “The Limits of Multiculturalism”, e-rooster.gr.

[35] Seyla Benhabib, (2010), “The Return of Political Theology”, Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol. 36 nos 3-4, pp 451-471

[36] Lauren Weiner, (2004), “Islam and Women-Choosing the Veil and other paradoxes”, Policy review, October-November 2004

[37] Fatima Mernissi, (1987), Beyond the Veil:Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society, Indiana University Press, revised edition 1987. Βλ. και, Άννα Καραμάνου, 2014, Europe and Women’s Rights. Europeanization in Greece and TurkeyPapazisis Publishing, pp. 402-403

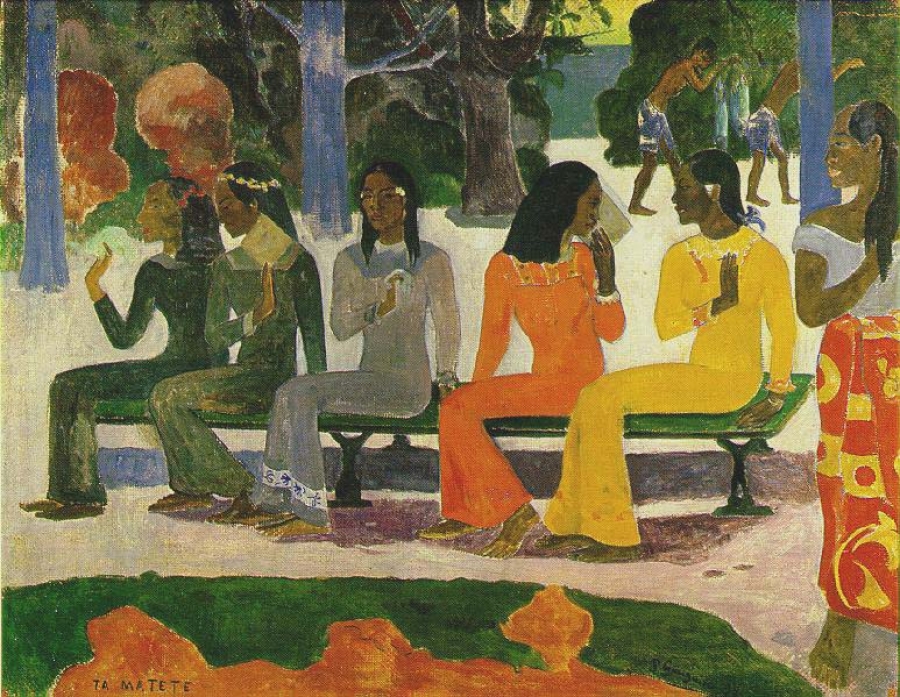

The table accompanying the text is: Gauguin, Paul (1849-1903) *Turgaus diena*