The Peaceful Uprising of Female Sapiens 1821-2021

CONFERENCE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF GREEK WOMEN SCIENTISTS

«The role of the Greek woman in the revolution of 1821»

Speech by Anna Karamanou

PhD in Political Science & Public Administration, NKUA

Former Member of the European Parliament – Chair of the FEMM Committee

The Peaceful Uprising of Female Sapiens 1821-2021

Brief CV:

Anna Karamanu was born in Pyrgos, Ilia, on May 3, 1947. She worked for 23 years at OTE (Hellenic Telecommunications Organization) and served as General Secretary of OME-OTE. She participated as a national expert in two gender equality policy networks of the European Commission. She was a Member of the European Parliament from 1997 to 2004. She was elected to the presidency of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (PES) Parliamentary Group and served as Chairwoman of the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) in the European Parliament.

She was awarded the İpekçi Peace and Friendship Award in 1999 for her contribution to the Greek-Turkish rapprochement. She is a member of the Greek Political Science Association, the Association of Greek Women Scientists, and the Political Women’s Union.

She studied at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens: a degree in Greek and English Philology, a Master’s in European and International Studies, and a PhD in Political Science and Public Administration.

She has authored the books: 200 Years of Greece. The Peaceful Uprising of Female Sapiens 1821-2021 (Armos Publishers, 2021), Europe & Women’s Rights: Europeanization in Greece & Turkey (Papazisis Publishers, 2015), and The Greek Woman in Education and Employment (OAED Publishers, 1984). She contributes to many collective publications and writes articles for magazines and newspapers.

Abstract

This work is based on my book, The Peaceful Uprising of Female Sapiens 1821-2021 (Armos Publishers). My goal is to provide a comprehensive picture of the major historical events of the 200 years of the modern Greek state, incorporating the silenced feminist struggles into the history of our country. I deliberately use the term “sapiens” because it means wise, prudent, sensible, knowledgeable, which are the essential characteristics of the human species (homo sapiens), with two equally valued genders. The issue of women’s rights and the theory accompanying it was the cause and struggle of half of humanity—the female sapiens—who had the courage to rise up and challenge the male monopoly, along with the social stereotypes and irrationality that accompany it. I also use the term “uprising” because it signifies, first, the notion of movement (as in a movement) and, second, the concepts of space and time, just as the feminist movement was. The term feminism encompasses the political action of women with the aim of eliminating injustice, violence, inequalities, and exclusions against them.

It is a fact that our historians have not honored, as they deserved, the contribution of Greek women in the 1821 Revolution, their participation in the glorious Balkan Wars which doubled the size of Greece, their noble struggle for the modernization of the state, equality in education and work, and gender freedoms and justice. Female fighters who sacrificed everything for their country were ridiculed and ignored by the State and by History. Small groups of pioneering educated women have written the history of feminist struggles in Greece for 200 years, under conditions of harsh patriarchy. The heroines of 1821 were sidelined! They were not recognized, neither in their right to govern the newly established state, nor in education, nor in work or entrepreneurship. They remained without freedoms, isolated in the family hearth, under the authority of male sapiens. Women were ignored by all the Constitutions before and after the liberation, until 1975, when the equality of Greek men and women was constitutionally guaranteed, and when, in 1983, the New Family Law left behind the Ottoman legacy. It is very characteristic and true what our national historian Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos wrote: the history of Greece has become like the sacred monasteries of Mount Athos, where no female of any kind is allowed to enter. This historical gap is covered by my book and my presentation at the SEW Conference.

INTRODUCTION

The Greek rebellion against the Ottoman Empire is the pinnacle historical event of our country. It is the first of Europe’s national revolutions to achieve complete success, with the participation of female fighters, and the first victorious war of independence by a subjugated people against imperial power. My book, Η ειρηνική εξέγερση των θηλυκών σάπιενς 1821-2021 (Armos Publications), presents the historical, social, cultural, and political context in which the struggles for liberation from the Ottomans and the foundation of the newly established nation-state developed, as well as the beginning and evolution of the fight for the fundamental rights of women and gender equality. My presentation for the 200th anniversary at this important SEW conference is extremely concise.

)The 200th anniversary compels us to ask: What would Greece be like today if half of its human potential had not been excluded from the country’s economic and political life from the very beginning? Why, even today, does 21st-century Greece remain so deeply patriarchal, so primitively misogynistic? What would have happened if Manto Mavrogenous, Boumpoulina, and other female revolutionaries, instead of being sidelined and vilified, had participated in the national assemblies and later in the leadership of the newly established nation-state? I found no participation or signature of Boumpoulina, Manto, or any other woman in the institutions, constitutions, assemblies, and decisions for the struggle and leadership of military operations, as recorded in the Archives of the Greek Rebirth (Paliggenesia) 1. Why, then, did the National Assembly (of men) exclude women from the “universal” right to vote in 1844 and from its constitutional recognition in 1864? Did the women deserve such unjust treatment? Why did the newly founded Greek state avoid leading and pioneering globally by recognizing the rights of women and their magnificent voluntary participation in the Revolution? How much did Greece’s development cost due to the political system’s refusal to harness the precious human potential represented by women? I attempt to answer these and many other questions, with evidence from the struggle of women for freedom, equality, and dignity. Unfortunately, today, 21st-century Greece has one of the lowest female employment rates in the European Union and ranks last in the EU Gender Equality Index (EIGE-2020). Without knowledge of history, it is impossible to understand the ongoing gender inequality, the unequal distribution of responsibilities and duties in managing political, social, and economic issues, violence against women, femicides, sexist language, sexual harassment, and the explosion of the #MeToo movement.

The armed uprising: the historical and ideological-political context.

The 1821 Revolution is the first uprising that challenged in practice the Holy Alliance and the famous 1815 Vienna Agreement. The Greeks, both men and women, rose up against Ottoman rule, motivated and inspired by the ideas and great upheavals that had preceded in Europe and America: the European Enlightenment, the Declaration of Independence of the USA (1774), the French Revolution (1789), and the Modern Greek Enlightenment. Europe played a dominant role in the ideological pursuits of the leaders of the Greek Revolution and was a decisive factor in both the new orientation and international position of the country, as well as in its internal politics. The European identity also served the goal of distancing the Greek community from its previous identification with the East and the Asiatic conqueror 2. It is clear that the identification of the Greeks with other Europeans and the Greek diaspora was neither self-evident nor accepted without opposition.

The ideological and political processes of Europe nurtured a generation of Greeks in the diaspora, most notably Rigas Velestinis and Adamantios Korais, who placed freedom as the supreme value and aimed at the revival of ancient Greek glory. Their goal was the search for a common ancestry with the Ancient Greeks and the elevation of antiquity as a key link for national awakening and unity. Rigas’ vision against Ottoman despotism and the creation of a multinational, democratic, and liberal state is reflected in four key texts: the Revolutionary Declaration, the Rights of Man, the constitutional charter (Constitution) of the Greek Republic, and the Thourios (a revolutionary anthem). Notably, in the Rights of Man, Rigas included the education of women: “schools for male and female children“, while in the Constitution, he referred to the right of women to bear arms 3. In this revolutionary current of thought and action, the conservative and authoritarian governments of Europe reacted, led by the Austrian Chancellor Clemens von Metternich (1809-1839), creator of the Holy Alliance and a fierce opponent of any liberal idea 4.

In this climate of conflict between conservative and modern ideas, the boldest Greeks decided to take their destiny into their own hands, founding the Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends) in 1814 in Odessa, Russia, where there was a strong Greek community, with the aim of “Liberating the Homeland.” In April 1820, Alexandros Ypsilantis assumed leadership. His mother, Elizavet Ypsilantis, known as the “foremother of the Filiki Eteria,” financed the struggle. The Greek War of Independence began under Alexandros Ypsilantis on February 24, 1821, in Iași, Moldavia, and concluded with the signing of the three Protocols of Independence on January 22 – February 3, 1830, in London. Thus, Greece, which had disappeared from the political map for centuries, re-emerged on the international stage 5. However, these great heroic moments alternated with dark periods of quarrels, civil wars, and defeats.

The untimely death of the nation-liberator Rigas Feraios (1797) deprived Greece of a great activist-intellectual and the feminist movement of a rare ally. However, his message, even after his excommunication by the Church and his assassination, reached many men and women who joined the liberation struggle against the Ottomans. Laskarina Bouboulina, Manto Mavrogenous, Eleni Vassou, Zambeta Kolokotroni, Sevasti Xanthou, Akrivi Tsarlamba, Domna Visviki, Asimo Gouraina, Stavriana Savaina, Panorea Voziki, Maria Palaska, the women of Souli, the women of Macedonia, the women of Mani, the women of Asopos, the women of Missolonghi, the women of Chios, the women of Naoussa, Despo Sechou-Botsi, Moscho Tzavella, and Haido Sechou are only some of the many women warriors who contributed voluntarily and significantly to the struggle. Yet, as is often the case in patriarchal and underdeveloped societies, the contributions of these women were not only unappreciated but met with fierce resistance when they sought recognition of their fundamental human rights. After liberation, they were placed under the authority of the male family members 6.

Research into the lives and actions of women during the 1821 Revolution is of great interest. Life in the countryside and in remote mountainous regions under harsh conditions has inspired many writers and biographers. Thousands of women lived as slaves in harems or in the homes of the wealthy. Women from lower social classes, with no access to education, lived in ignorance and superstition. Historians and travelers of the era dedicated praiseworthy passages to Greek women. Eyewitness accounts, especially from foreigners rather than Greeks—poets, writers, philhellenic fighters, historians, and painters—attest to their patriotism and heroism.

The peaceful revolution of the female sapiens:

Priority in education

The peaceful feminist revolution, as a continuation of the armed struggle of women against the Ottomans, essentially began in 1829, during the time of Kapodistrias, with the establishment of the first school for girls. It was at this point that women began to be educated. Therefore, feminism, in its journey

of two-hundred years has been the work of the most educated women. The pioneering women of the 19th century, primarily teachers, gave voice to demands on behalf of all women, actively participating in the reconstruction of the new nation-state and its progress. They fought for the promotion of their rights in a society that considered the education of women unnecessary.

The first girls’ school (parthenagogio) was established by the Philomuse Society of Athens in 1825 at the Acropolis. During this period, Syros was at the forefront. In 1827, two mutual teaching schools for boys, one for girls, and one mixed-gender school were operating, thanks to private initiative. In Maria Aivalioti’s school, 25-30 girls were enrolled. In the school of the Protestant missionary Christian Ludvig Korck, 170 boys and 80 girls attended in August 1828, and a year later, there were 350 boys and 170 girls. In 1829, the municipality founded a mutual teaching school for girls. A key figure in the establishment and operation of this school was Evanthia Kaïri, the first intellectual woman of free Greece, who had settled in Ermoupolis in 1824. She remained there for about 15 years, teaching as a schoolmistress. (7) Adamantios Korais also contributed to Kaïri’s education by guiding her through correspondence. In Ermoupolis, the Higher Girls’ School was also founded, the first secondary school for girls, which for many decades also functioned as a teaching institution, providing trained teachers.

In 1831, the operation of the Hill school began, followed by the Zappeio and Arsakeio schools. In 1836, the Education Friendly Society was founded with the aim of elementary education, and later it established a girls’ school-teacher training institution. One of its graduates, Kalliopi Kechagias, founded the first association named the “Ladies’ Society for Women’s Education” (1872). (8)The comprehensive design of the educational system, at all levels, based on Western models, was implemented with the arrival of the Bavarians and the reign of Otto (1832-1862). Greece established compulsory primary education in 1834. However, superstitions and prejudices against female education hindered the integration of girls into schooling. In her autobiography, Elena Venizélou, the wife of Eleftherios Venizélos, writes: “In the 19thcentury, girls passed from their father’s house to their husband’s house… I never went to school… With teachers who came to the house, I learned languages and speak many fluently. They taught me geography, history, literature, and music 9” The home lessons were, of course, only available to the daughters of upper-class and Europeanized families, like Elena Venizélou’s. Female education was initially recognized only in terms of its ability to contribute to the better fulfillment of the woman’s role as a wife, mother, and housekeeper, through only primary education 10. However, the fighters of 1821, in their plan for the foundation of the new nation-state, did not exclude women from education and public schooling, as evidenced by the writings of Rigas, the Declaration of the Peloponnesian Senate of 1822, and the Constitution of the Third National Assembly of 1827, which provided for a free educational system in three levels for boys and girls 11.

Public Education (1830-1922) – literacy rate of men and women.

(DouglasDakin, H ενοποίηση της Ελλάδας, 1770-1923, Μ.Ι.Ε.Τ, Αθήνα 1984, Παράρτημα Δ΄)

| Year | Literate men | Literate women |

| 1840 | 13% | |

| 1869 | 29% | 6% |

| 1910 | 50% | 20% |

| 1922 | 56% | 27% |

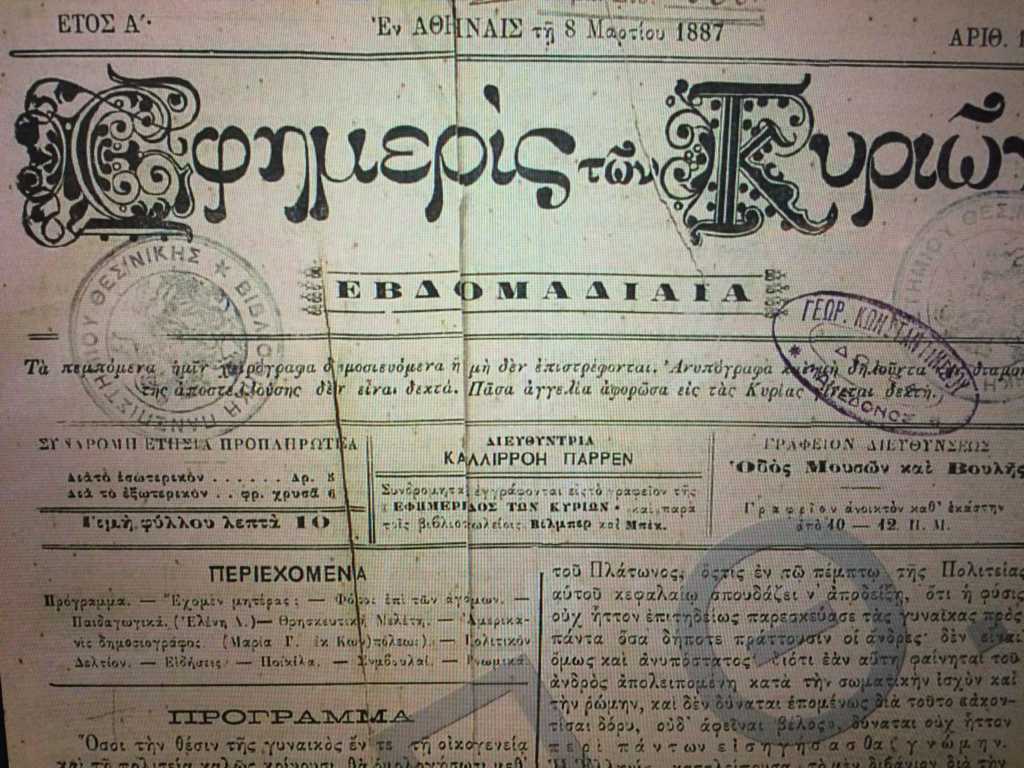

The Newspaper of the gentlemen: March 8 1887

In the negative atmosphere for women’s demands in post-Ottoman Greece, the first women’s magazines were published, and the first women’s organizations were founded. Greek women contributed to the building of the Greek nation-state, with economic and socio-political terms, through their actions and struggles. On March 8, 1887 (this is the Greek March 8th!), *I Efimeris ton Kyrion* (The Ladies’ Newspaper) was published, which shook the entire Greek patriarchy. It continued to be published for 30 years. This was the great peaceful uprising of the “female sapiens” of the 19th century against the patriarchal order of things, led by Kallirroi Parren (1861-1940), the first and most prominent Greek feminist, journalist, and writer. The message was clear: Rights and participation in public life! “Men should not have the monopoly on thinking rightly and judging,” wrote Kallirroi Parren in the first issue, immediately demanding the inclusion of women in the political sphere and decision-making processes.

In Greece, the sacred patriarchal values and the different criteria for the two sexes remained largely unchanged in the face of the pressures of modernity. The confinement of women to household duties was a matter of honor and social status for bourgeois and middle-class families. Only women from lower economic strata worked outside the home, and even then, only if they did not neglect the care of their families. They typically provided unpaid labor in family businesses. Poor women worked as servants or housekeepers in middle and upper-class households, or as workers in textile, clothing, and tobacco industries. The lower status of women in education and employment, as can be understood, was closely linked to their subordinate position within the family, the gendered division of labor, and the lack of recognition of individual autonomy and political rights. Forced marriages and honor crimes were common and remained largely in place, along with the institution of dowries, until Greece’s accession to the European Union.

At the end of the 19th century, when Charilaos Trikoupis was attempting to modernize Greece, it was only the circle of Kallirroi Parren that fought fiercely for the improvement of women’s education, decent employment, and the inclusion of girls’ secondary education into the public educational system, a demand that was fulfilled in 1917. In September 1890, the first female student, Joanna Stefanopoli, of French origin, was admitted to the Faculty of Philosophy. Her example was timidly followed by others, so that by 1900, around twenty female students were enrolled at the University 12. Sophia Laskaridou was the first female student of the School of Fine Arts. In 1908, Angeliki Panagiotatou, the first female student of Medicine, was elected assistant at the University of Athens in the Chair of Epidemiology. When she ascended to the podium for her first lecture, she faced the disapproval of the male students: “To the kitchen! To the kitchen!”. 13 In 1896, during the revival of the Olympic Games, women were banned from participating. However, the women, led by Kallirroi Parren, took part in the “unsuccessful” war of 1897, offering valuable medical services. With their mass participation in the war, the women overturned basic beliefs that restricted the role of women to the private sphere of reproduction and family care. The Greek women, inspired by the Great Idea and the irredentist visions, participated with enthusiasm. In general, this group of feminists challenged the limits of “proper” or “naturally” justified actions for women, focusing on “equality” and shifting the women’s issue to the realm of human rights 14.

20th CENTURY: Greece on a path of reconstruction and transformation.

The struggle for social and political rights of women in the 20thcentury was a grand historical and political process. During the first half of the 20th century, the battles for women’s suffrage peaked in both Europe and Greece. In 1908, the National Council of Greek Women was established, which included 80 Greek and Cypriot women’s organizations. On February 19, 1911, Kallirroi Parren founded the “Lyceum of Greek Women.” The Balkan Wars halted the activities of women’s associations, as well as their publications, because women devoted all their energies to supporting the military operations. Women felt it was their moral duty and sacred obligation to contribute their forces to Greece’s national liberation struggles. Their contribution, particularly in providing medical care for the wounded, organizing food distributions, and transporting weapons, was invaluable. Women played an active role in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, helping secure victory and the doubling of Greece’s territory. Under the inspired leadership of Venizelos, the romantic vision of the Great Idea seemed to enter the realm of reality. This was followed by World War I, the disagreement between Venizelos and King Constantine, the national division, and eventually the Asia Minor catastrophe in 1922 15.

With the end of World War I, the top demand for women’s political rights was presented for the first time with such clarity and determination. On January 16, 1920, the Women’s Rights Association was founded. Three years later, in 1923, the magazine O Agonas tis Gynaikas (The Struggle of Women) was published under the initiative of Avra Theodoropoulou. The Association of Greek Women Scientists (AEES), with members who were Greek female university graduates, was founded in 1924 and has been continuously active, making significant contributions. The period from 1920 to 1940 was crucial for feminist struggles, the democratization of the political system, and the achievement of the right to vote. On July 8, 1929, Venizelos, in a speech in Parliament, officially recognized gender equality. He expressed his belief in women’s abilities and consented to granting women the right to vote in the upcoming municipal elections. The decree was issued in February 1930, and some women, literate and over 30 years old, were granted electoral books and the right to vote in the municipal elections16. In the local elections of 1934, only 240 women voted. It is noteworthy that during the interwar period, particularly in the 1930s, when militarism, National Socialism, and aggression had reached new heights in Europe, Greek women, through their international action, focused on issues of disarmament, peaceful resolution of differences, and compromise solutions.

In 1928, 31.5% of workers in the industry were women, and 12.5% worked in public services. During the interwar period, significant percentages of women were engaged in traditional female professions (such as maids and teachers) 17. Discrimination against working women intensified during the 1930s. Private sector unions opposed the inclusion of women in male-dominated sectors, fearing that it would lead to male unemployment (e.g., in the tobacco industry). Between 1936 and 1940, the dictatorial regime institutionalized wage discrimination in the private sector. The law that introduced collective labor agreements for the first time established lower wages for women doing the same work as men. In any case, women’s wage labor was characterized by low pay, lower hierarchical positions, limitations in salary and career progression, temporariness, and a clear separation from male workers 18. The first efforts to eliminate legal gender discrimination began in the 1950s, with the ratification of the New York International Convention in 1953. Gender equality in labor relations would not be achieved until much later, after Greece’s full accession to the EU in 1981 and the adoption of Community legislation.

Among the most significant milestones of the 20th century are the declarations and international conventions of the United Nations aimed at establishing a legal framework that protects human rights and gender equality in various sectors: education, employment, marriage, and individual and political rights. Greece ratified the UN conventions for political rights equality and equal access of both genders to all public offices in 1952. With Law 2159/1952, Greek women were granted the right to vote and stand for election, and with Law 3192/1955, they gained the right to be hired for all public services, except for the military and the Church. Eleni Skoura became the first female Greek Member of Parliament, running as a candidate for the political party of the Synagermos. She was elected on Sunday, January 18, 1953, in the Thessaloniki district. It is worth noting that the first female Member of Parliament had opposed women’s suffrage between 1947-1949, when the female vote was considered dangerous for the nation.

The modern history of Greece and Europe has been marked by major political milestones: the Treaty of Rome in 1957, with Article 119 on equal pay, the Association Agreement between Greece and the EEC (1961), free education in 1964 19, the seven-year dictatorship of 1967, the May 1968 protests, the Polytechnic uprising, the post-junta period, the pro-European government of Konstantinos Karamanlis, the abolition of the monarchy, the legalization of the Communist Party (KKE), the 1975 Constitution ensuring equality for Greek men and women, the emergence of new feminist organizations, the flourishing of the feminist movement, Greece’s accession to the European Union in 1981, the adoption of European Union principles by the government of Andreas Papandreou, the new Family Law in 1983, the Amsterdam Treaty in 1999, the pan-European campaign against gender-based violence in 1999, Greece’s entry into the Schengen Area and the Euro under the government of Kostas Simitis, the Church-State conflict over identity cards, the 2001 Constitutional revision, the Lisbon Treaty, the Cohabitation Agreement, the economic crisis, the Prespa Agreement, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Greek MeToo Movement, and the European Strategy for Gender Equality 2020-2025 20.

General Conclusion: The historiographical research of the past 200 years, through available historical sources, provides ample material for self-knowledge and reflection. It evokes pride and tears! Joy and disappointment! The participation and courage displayed by women in the armed revolt against the Ottomans was a practical and conscious challenge to the patriarchal order, initiated by the women themselves. Gender divisions and stereotypes were abolished on the battlefield. The research demonstrated that women’s feminist organizations, from the 19th century to the present day, are the most important civil society organizations. With universal values and human rights as their banner, they dynamically challenge entrenched power relations between the sexes, cultural dualism, xenophobia, and the monolithic nature of tradition. After long and arduous struggles, feminists forced the patriarchically structured political system to implement reforms and changes that strengthen democracy, the European profile of our country, the rule of law, progress, and socio-economic development: Modern Civil, Criminal, and Labor Law, changes in education, laws and structures to combat violence against women, decriminalization of abortion, criminalization of rape both inside and outside marriage, the Cohabitation Agreement, and women’s entrepreneurship. The election of Katerina Sakellaropoulou to the highest state office, as the President of the Hellenic Republic, is the culmination of 200 years of persistent feminist struggles. However, the democratic deficit in gender equality remains. The triple elections of 2019 confirmed the direct or indirect exclusion of women from political power. At the same time, the enforced confinement at home due to the pandemic multiplied domestic violence, hate crimes, and femicides. The #MeToo movement, which arrived belatedly in Greece, succeeded in freeing the voices of women. Now, we denounce, share, mobilize public opinion and the political system, classify femicides as heinous gender-based crimes, achieve modernization of the laws, and train justice system stakeholders. What remains is to close the gender power gap, which is the breeding ground for all forms of violence, imposition, and inequality against women! The mobilization of women themselves, solidarity, and the elimination of competition between us is essential.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Αβδελά, Έφη, «Στοιχεία για την εργασία των γυναικών στο Μεσοπόλεμο: όψεις και θέσεις» στο Γιώργος Μαυροκορδάτος- Χρήστος Χατζηιωσήφ (επιμέλεια), Βενιζελισμός και Αστικός Εκσυγχρονισμός, Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Κρήτης, Ηράκλειο, 1992, σελ.195 (16)

- Αρχεία της Ελληνικής Παλιγγενεσίας, 1821-1832, Έκδοση της Βιβλιοθήκης της Βουλής των Ελλήνων,1973 (1)

- Βαρίκα Ελένη, Με διαφορετικό πρόσωπο,εκδ. Κατάρτι 2000, σελ.248 (13)

- Βενιζέλου, Έλενα, Στη σκιά του Βενιζέλου, Εκδ.Ωκεανίδα, 2002, Αθήνα, σελ.19. (9)

- Βερέμης Θάνος και Γιάννης Κολιόπουλος, Ελλάς η Σύγχρονη Συνέχεια – από το 1821 μέχρι σήμερα, εκδ. Καστανιώτη, , 2006, σ.41-48, (2 )

- Δαλακούρα Κατερίνα & Σιδηρούλα Ζιώγου-Καραστεργίου, 2015, «Η εκπαίδευση των γυναικών Οι γυναίκες στην εκπαίδευση (18ος-20ός αι.) Κοινωνικοί, ιδεολογικοί, εκπαιδευτικοί μετασχηματισμοί και η γυναικεία παρέμβαση», Ελληνικά Ακαδημαϊκά Ηλεκτρονικά Συγγράμματα και Βοηθήματα, www.kallipos.gr (7)

- Δημαράς, Αλέξης, Η Μεταρρύθμιση που δεν έγινε, εκδ. Το ΒΗΜΑ, Alter Ego AE, 2017 (11)

- Ελληνική Νομαρχία, Ανωνύμου Έλληνος, 1806, ήτοι Λόγος περί Ελευθερίας, Κείμενο-Σχόλια-Εισαγωγή, Γ. Βαλέτας , τέταρτη έκδοση, Αποσπερίτης 1982, σελ. 8α (3 )

- ΕΤ1, εκπομπή «Στη μηχανή του χρόνου», 23.03.2020, (4)

- Ζαχαράκης, Νίκος, «Η Εκπαίδευση στα πρώιμα χρόνια της Ερμούπολης», Συριανά Γράμματα, τεύχος 6, περίοδος Β, Δεκέμβριος 2019 (7)

- Καλύβας, Στάθης, Καταστροφές & θριάμβοι, Oxford University Press, εκδ. Παπαδόπουλος, 2015, σσελ. 49-57 (2) (17)

- Καραμάνου Άννα, Η Ειρηνική εξέγερση των θηλυκών σάπιενς 1821-2021, εκδ. Αρμός, 2021, σελ.351-358 (21)

- Καραμάνου Άννα, Η Ευρώπη και τα Δικαιώματα των Γυναικών, εκδ. Παπαζήσης, 2015, σ. 145-153 (19)

- Καραμεσίνη, Μαρία, Γυναίκες, Φύλο και Εργασία, εκδ. Νήσος, 2019, σελ. 36 (18)

- Κωστής, Κώστας, Τα κακομαθημένα παιδιά της ιστορίας, εκδ. Πολις, σελ. 159-165 (2)

- Λάππας, Κώστας, Πανεπιστήμιο και φοιτητές στην Ελλάδα κατά τον 19ο αιώνα, Ιστορικό Αρχείο Ελληνικής Νεολαίας Γ.Γ. Νέας Γενιάς, 2004, σελ. 251-253 (12)

- Μαυρογορδάτος Γιώργος, 1915 Ο Εθνικός Διχασμός, εκδ. Παττάκη, σελ. 33-37 (15)

- Μόσχου-Σακορράφου, Σάσα, Η Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Φεμινιστικού Κινήματος, Αθήνα, 1990, σ. 22-23 (6)

- Μπακαλάκη Αλεξάνδρα και Ελένη Ελεγμίτου, Η Εκπαίδευση «εις τα του Οίκου» και τα γυναικεία, καθήκοντα, Ιστορικό Αρχείο της Ελληνικής Νεολαίας, Γενική Γραμματεία Νέας Γενιάς, Αθήνα 1987, σελ. .18 (10)

- Ρήγας Βελεστινλής, (1757-1798), Τα Επαναστατικά. Επαναστατική Προκήρυξη. Τα Δίκαια του Ανθρώπου, το Σύνταγμα, ο Θούριος, Ύμνος Πατριωτικός . Έκδοση της Επιστημονικής Εταιρείας Μελέτης «Φερών-Βελεστίνου-Ρήγα», Αθήνα 1994. (3)

- Υπουργείο Προεδρίας, Συμβούλιο Ισότητας των δύο Φύλων, «Το Γυναικείο Κίνημα στην Ελλάδα» – φυλλάδιο στα Ελληνικά και Αγγλικά, 1984 (8)

- Χρήστου, Θανάσης, Πολιτικές και Κοινωνικές Όψεις της Επανάστασης του 1821, εκδ. Παπαζήση, 2013, σ.21 (5)

- Avdela Efi & Aggelika Psara “Engendering Greekness, Women’s Emancipation & Irredentist Politics, in 19th Cent. Greece” Mediterranean Hist. Review, Vol. 20, No1, June 2005, p.67-69(1 4)

- Clogg, Richard, Συνοπτική ιστορία της Ελλάδας, 1770-200ο, εκδ. Κάτοπτρο σελ.32-33 (3)