THE POSITION OF WOMEN IN THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY AND GENDER POLICIES IN UNIVERSITIES.

NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS

Undergraduate Program of Studies on Gender and Equality Issues

THE POSITION OF WOMEN IN THE ACADEMIC COMMUNITY

AND GENDER POLICIES IN UNIVERSITIES

11-12 December 2004

Anna Karamanou

former MEP (Member of the European Parliament)

INTRODUCTION

Sciences and technology, as well as the position of women in the academic community, have repeatedly been identified as critical areas for promoting the role of women and gender equality. However, despite the fact that the need to integrate the gender dimension into all sciences and all policies, as well as into the new Information Society, has been demonstrated, unfortunately, so far the public debate has mainly focused on the economic consequences, ignoring gender.

The history of gender studies at the university level is also very recent. Their emergence can be traced to the late 1960s in Europe and the 1990s in Greece. During the same period, criticism began against the academic community for the way knowledge was produced, which excluded the experiences, interests, and particular characteristics of women.

Women are underrepresented in most scientific fields, at all levels of the scientific hierarchy, and they have fewer opportunities to receive funding for research. As stated in the European Parliament report “Women and the Information Society,” in the EU, of the 500,000 researchers working in industry, only 50,000 are women. At universities and research centers, the percentage of women ranges between 1/4 and 1/3, while at the highest levels and decision-making bodies, the percentage is less than 12%.

Through this brief presentation, I will attempt to demonstrate that this gender asymmetry, beyond violating the principle of equality, contradicts the modern needs for cultural, economic, and social development. I will also present data that will show that science and research are not gender-neutral.

PREJUDICES AND DISCRIMINATIONS AGAINST WOMEN

It is a common belief that when women are in conditions of true equality and meritocracy, they perform just as well or often better than men. For example, in most European countries, female university graduates outnumber male graduates (in Greece, 62% of undergraduate students are women). Nevertheless, among the academic staff of European universities, and especially in the highest ranks and decision-making bodies, men dominate. The scientific community fully reflects patriarchal social structures.

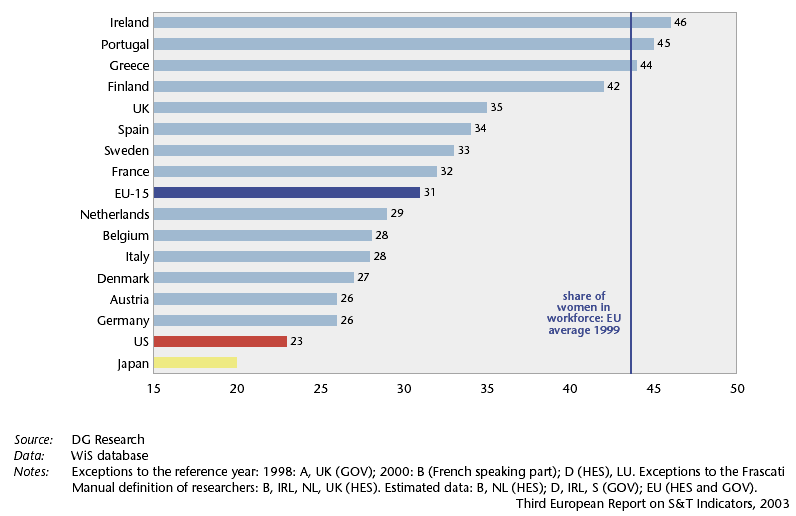

The percentage of female workers and researchers in European higher education institutions averages 31%, compared to 23% in the United States and 20% in Japan. It is interesting to note that four European countries—Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Finland—have female researchers in percentages exceeding 40%. In countries with relatively new institutions and universities, such as the four mentioned above, as well as Cyprus, women found the opportunity to showcase their abilities and claim recognition. In contrast, in countries with established systems in education and science, despite the quality of scientific work produced by women, men dominate. Germany, ranking last in the EU with 26%, is a very characteristic example.

A recent report by the European Commission titled “Building Excellence through Equality” finds that female scientists face discrimination even in terms of their salaries, the type of contracts they have (most fixed-term contracts are held by women), their professional advancement (which is delayed, more difficult, and rarer compared to men), while they are almost entirely absent from the highest ranks and prestigious positions.

These discriminations are certainly not based on an objective assessment of women’s abilities, but on prejudices and stereotypical behaviors. A study conducted in the United States on the “productivity” of female and male scientists, using the quantitative criterion of their article publications in scientific journals, provides a striking example. The study found that the majority of unpublished articles were written by women, while the majority of published articles were written by men. Therefore, women conduct research, produce work, and wish to subject it to the judgment of the scientific community. However, this opportunity is not given to them, resulting in hindered professional advancement and the perpetuation of discrimination against them.

It thus becomes clear that, no matter how significant the progress women have made in recent years in every field, there are still many important steps that must be taken to achieve true equality. The European Commission has set as its goal the consideration of the gender dimension in the Sixth Framework Program for Equality, which covers the period 2002-2006, and encourages increasing women’s participation in research programs to no less than 40%. As is natural, when women are given the opportunity to prove their abilities, the benefit is not only for women but also for society itself, which achieves better utilization of its available potential through a meritocratic expansion of the population base that drives economic and social development.

CHOOSEORLOOSE

It is a fact that women who are interested in their professional careers face, at some point in their journey, the dilemma of choosing between family and career, known as the “choose-or-lose” dilemma. Despite the differences observed between European countries, the data generally shows that, in many countries, female scientists are less likely to have a family, and in any case, they pay the price for their choice—either they do not have children, or they do not have the career they desire. In contrast, having a family seems to positively impact a man’s prospects for career advancement. It is characteristic that men with three or four children are much more likely to rise to the highest ranks of their profession compared to men without children or a family. The exact opposite is true for women. That is, women with three or four children are found at the lowest levels of the hierarchy, while childless and single women are at the highest.

While it is a common belief that for some women, the inability to advance professionally is the result of choices related to family, no one has thought to link the inability of some men to advance professionally with specific choices of a similar social nature. The absence of such reflection highlights the vast scale of the problem, as it is still taken for granted that the woman will bear the greater part – if not all – of the family responsibilities and, in her remaining time, can also take care of her career.

WOMEN AND SCIENCE

Expenditures on research and technology absorb the largest portion of the community budget, after the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Structural Funds. Since the majority of researchers and decision-makers are men, it is very likely that women’s interests, in specific areas, are not taken into account. Medical researchers seeking preventive treatments for diseases focus almost entirely on men. As Marilyn French writes in her book *The War Against Women*, in the United States, research on heart disease and the role of cholesterol was based exclusively on studies of men, meaning that diets and medications promoted for lowering cholesterol can harm women. When aspirin was studied as a drug that could prevent heart disease, doctors tested it on 20,000 men and not a single woman. The treatment of heart disease is centered on men, while it has been found that more women than men die after coronary bypass surgery.

About a year ago, in an open session/public dialogue organized by the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality of the European Parliament, the scientists who were invited confirmed that very little money is allocated for research on diseases that particularly affect women, such as osteoporosis, the consequences of menopause, and breast cancer. In other words, we find that even in the fight against diseases, there are gender-based discriminations.

However, while the medical establishment generally disregards women’s health, it is not indifferent to motherhood. It is well known that a global effort has begun to control women’s reproductive functions through the use of new technologies. It is clear that the sciences are not neutral with regard to gender. This is why it is necessary to find the right strategy and means for more women scientists to participate in research and knowledge production, not to stop progress, but to give a humanitarian dimension to the sciences and technology, and to protect the rights and future of women and the new generation.

GENDER POLICIES IN UNIVERSITIES

Until the 1970s, universities and social sciences generally ignored gender. The “people” they studied were mostly men, and the topics were aspects of society that primarily concerned men, such as economic and political power. In the gender-blind sociology, women did not exist, until the early 1970s, except as wives and mothers within the family. The differences and inequalities between men and women were not recognized as an issue of sociological interest, nor as a problem that needed to be addressed.

During the 1970s, thanks to the criticism and pressure exerted by feminists, the humanities and the arts initially began to show increasing interest in gender. Particularly, female sociologists started to examine discrimination and inequalities, filling in the gaps in knowledge. Attention gradually shifted to areas that particularly concerned women, such as paid work, domestic labor, motherhood, and male violence.

In academic fields such as, for example, English Literature, scholars began to attack the hegemony of the “greats” of literature, who completely excluded women, without even bothering to address, at least in the slightest, the material and social conditions that hindered the emergence of “great” women in this field. At that time, in the 1960s and early 1970s, a critical mass of women in the humanities succeeded in creating fertile ground for feminist criticism. This was precisely the period when women’s studies began to develop as a specialized branch of academic interest in Europe and the United States. The first MA in women’s studies in Europe was launched by the University of Kent in 1980, followed by York and Warwick. In the United States, they had started in 1969 at some colleges and universities, though without particularly good preparation.

THE PUBLIC DEBATE IN EUROPE

In Europe, during the 1970s, an extensive international dialogue developed about the content and significance of gender studies. Many saw them not only as a challenge to the boundaries of existing knowledge and an opportunity for the development of new fields of study, but also as a legitimization of the different social and cultural experiences of women. At the same time, traditional forms of teaching and the relationships between professors and students came under the microscope of criticism.

Gradually, the field of women’s studies also clarified its identity. Instead of seeing its main task as critiquing traditional values and social stereotypes, it became the area where the knowledge produced by the patriarchal system was tested and re-evaluated. The practices and prejudices of academics became the subject of study. It is a fact that gender studies, as a distinct field of academic interest, contributed greatly to the strengthening of feminist knowledge and the critique that changes existing perceptions.

Of course, gender relations change, as does feminism as a political ideology, which changes and discovers new paths for exploration. Academic institutions have also changed over the past thirty years. Furthermore, gender studies is a field that has applications in the world beyond universities, since specialized activity in the academic environment can have multiplying benefits for both women and men, changing the way they think about themselves and the realities of their lives, both within the university and in society.

EUROPEAN POLITICS

At the European level, there have been no serious initiatives to strengthen gender studies, since educational policy falls under the responsibility of the member states. The effort to enhance the participation of women in science and research has begun just in recent years. In 1999, the European Commission, within the framework of the Fifth Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (1998-2002), launched an action plan to strengthen women scientists, with a strategy to promote research “by and for women,” in cooperation with the member states and other key stakeholders. This approach proved to be successful. The previous year (1998), the “ETANWorkingGrouponWomenandScience», was established, and its report, published in 2000, defines gendermainstreaming as a vital prerequisite for promoting excellence in science.

In November 1999, the Helsinki Group was established. and its first meeting took place in Helsinki under the Finnish Presidency, with the support of the Directorate-General for Research of the European Commission. The idea behind this initiative was to promote policies to strengthen the gender dimension in science and in the careers of scientists. The HelsinkiGroup, which involves 30 countries (including Israel and Iceland), has achieved quite a lot in a relatively short period of time. Of course, there is significant diversity among the various countries in their approach to the issue of “Women and Science,” as well as in the scientific support provided. In September 2003, the ENWISEGroup exclusively for the pre-accession countries of Eastern Europe.

In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, universities now have greater independence than in the past, while in the Scandinavian countries, there has been tremendous progress in terms of the gendermainstreaming. There are significant differences regarding gender balance in decision-making and policy formation, as well as concerning what constitutes science and scientific excellence, how budgets are allocated, who grants scholarships and awards, who appoints, and who decides on promotions. In all the countries of the Helsinki Group, to a greater or lesser extent, there is a lack of gender balance in positions of responsibility and decision-making. Another major issue also concerns the disproportionate abandonment of scientific careers by women, relative to their participation in education, in all the countries.

Finally, the issue of modernizing management and the policy of utilizing human resources by universities and research centers is raised. The HelsinkyGroup has worked on the collection of statistical data and comparative analyses, the promotion of positive actions, and the development of advisory plans and gendermainstreaming, but also for the exchange of experiences and successful practices. Above all, it has highlighted the importance and value of gender studies in universities, the academic arm of the women’s movement. These academic fields are very important for understanding both the position of women in the scientific community and the “leakage” from scientific careers, as well as the hidden institutional sexism.

Another area of action for gender studies is the effort to reintegrate women who have left or interrupted their careers back into the scientific community. This is very important also from the perspective of utilizing the investment made in their education. A major issue remains ensuring a balance between private life and scientific career, and whether scientists are also well-rounded individuals who allocate part of their time for others. A recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge found that more than half of academics had no caregiving responsibilities at all.

Is it really impossible to have a family and private life while also being a good scientist? We certainly need very good policies to ensure the balance between public and private life. At present, being male or female is crucial for a successful scientific career. One only needs to look at the statistics and the media to realize what gender studies have shown.

It is certain that the inclusion of more and more women in the fields of science and technology will instill in them the unique values associated with the female gender. The European structure itself is based on distinctly “feminine” values, such as resorting to dialogue and cooperation to solve problems, forming bonds between nations based on common interests, and pursuing agreements through negotiations. These principles, which, according to the JeanMonnet, constitute the counterbalance to the brutal resort to violence, and it is thanks to them that the success of the European Union project has been achieved. As long as we remain faithful to these principles, we have more hope for an even better Europe. Gender studies have a lot to offer in this direction.

sources:

- Manual on Gender Mainstreaming-European Commission

- Science and Society Action Plan

- Nancy A Naples «Feminism and Method»

- Sandra Harding «Discovering Reality»

- Sandra Kemp and Judith Squires «Feminisms »

- «Everywhere and Somewhere: Gender Studies.»

- Tersa Rees -First Results from the Helsinki Group

- «EU Integration and the Role of Women in Science and Technology» Anna Karamanou-Enwise Conference- Tallinn, 6-7.9.2004

Table 1: Percentage of female employees and researchers in Higher Education Institutions (1999).

Source: European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 259.

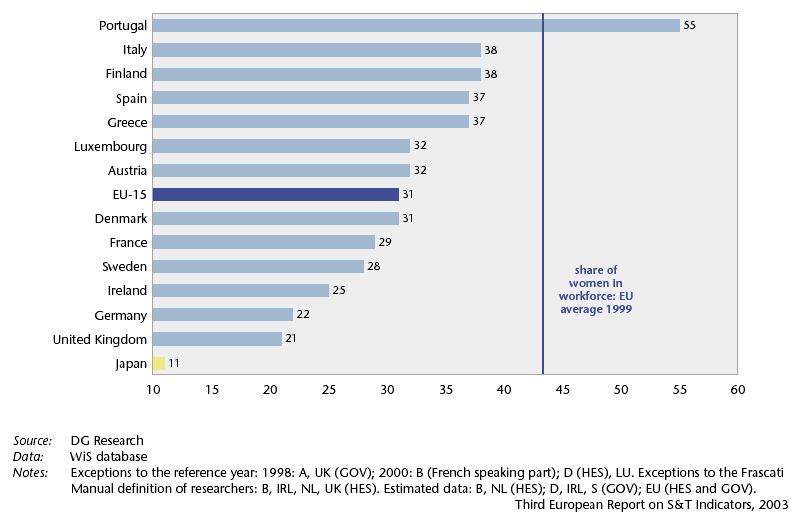

Table 1: Percentage of female employees and researchers in government positions (1999).

Source: European Commission, European Report on Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, Dossier III, Women in Science: What do the indicators reveal?, p. 259.